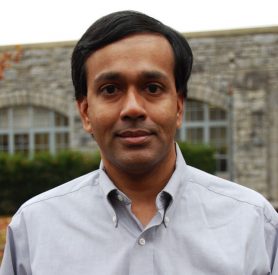

In a video call from the US, SolarPACES caught up with Ranga Pitchumani, Editor-in-Chief of Solar Energy, a leading journal in the field.

Dr. Pitchumani was the Chief Scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), SunShot Initiative, Founding Director of its Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) program, and Director of the Initiative’s Systems (Grid) Integration program. A former Ex-Co member of the IEA SolarPACES, he has also served as an advisor to several solar energy programs in different countries including the Australian Solar Thermal Research Initiative of ARENA. In his academic role, he is the George R. Goodson Endowed Chair Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Virginia Tech where he directs the Advanced Materials and Technologies Laboratory and has authored numerous scientific papers in the field of solar energy.

SK: How has CSP changed since you led the DOE SunShot program for the Obama administration?

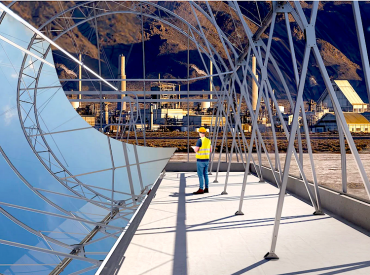

RP: The pursuit of making CSP cost-competitive with grid parity, that began with the SunShot Initiative, has advanced quite well. There has been a systematic exploration of the various options or pathways for Generation 3 CSP namely the liquid pathway (using molten salt as the heat transfer fluid and storage medium), the gas pathway (directly capturing concentrated solar energy using supercritical CO2), and the solid pathway (using particles for direct capture, transport and storage of concentrated solar energy). Of these, the particle pathway has emerged as a viable approach to realizing high-temperature next-generation CSP. Sandia is leading the development of the next-generation particle receiver and CSP system. There’s tremendous momentum in particle-based CSP now.

Apart from the engineering marvel and challenges in this technology, there’s a lot of interesting fundamental physics that we need to understand and incorporate into our traditional analysis. Particles are a new domain for CSP and likewise high-temperature Gen3 CSP brings unique challenges to particle flow, heat transfer, and interactions with confinement surfaces. So, it is an important learning and discovery exercise as we develop the technology driven by the science.

And we are just starting to “scratch the surface” of the problem.

SK: Literally, in some of your work..

RP: I have always argued that CSP is an amalgam of multiple disciplines, including physics, optics, chemistry, chemical engineering, mechanical engineering, materials science – and with particles also high temperature tribology. Now, more than ever, is a fertile opportunity for the broader community to engage in advancing this fantastic technology.

SK: Yes, it really is astonishing to me how many other disciplines are involved in particle CSP. How best to hoist sand up to the top of a tower is not what somebody imagines they’ll figure out when they get into concentrated solar research, right?

RP: Absolutely, absolutely. And to me, that makes it interesting and fun, because it keeps me young, because I am always needing to learn new things.

SK: Do your Virginia Tech students come from many kinds of engineering backgrounds?

RP: In my lab we have quite a mix. I have physicists, chemical engineers, mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, and materials scientists. It’s just getting the brightest minds to work on problems. It’s wonderful. My research group is passionate, whether I’m there or not. I mean, they’re not doing it because their supervisor gave them this problem. They’re doing it because they love it. And so they go above and beyond. And most of the time I’m learning from them.

It’s really a fantastic way to do work, because you excite them, you give them the broad picture, and say, here’s a big problem to solve. And they’re off. They’re not asking me what to do next. They are in the driver’s seat, and my role is to fuel their curiosity by asking the critical questions. It’s an extremely fun exchange. Quite unlike a classroom setting where the professor knows the answer to the problem and is testing to see if the student can arrive at the answer. Research is more of a two-way exchange. Very often, I am the student learning from them and discovering with them. These are the thought leaders, entrepreneurs and change makers of the future. I simply have the privilege of having them in my group now.

SK: That is great. It sounds really gratifying. So last time I covered your work, it was on coatings, if I recall. Has your focus always been on these physical surfaces?

RP: The nexus of materials and energy systems has certainly been one of the focus areas of the research in my lab. In our last conversation, we spoke about our work on surface innovations to tame corrosion attack of substrate alloys by molten chloride and carbonate salts at the Gen3 CSP relevant high temperatures. Following up on that, we showed through a rigorous technoeconomic analysis the impressive levelized cost reductions of over 60% compared to Haynes 230, enabled by the corrosion mitigation coatings on low-cost ferrous materials such as stainless steel, while offering corrosion protection on par with or better than the expensive Haynes alloy. So, with these coatings we developed, we can now use common materials like stainless steel, and they can withstand the worst of corrosive elements, such as molten chloride salts, at Gen3 CSP conditions.

We also spoke about our innovation on high temperature solar absorber coatings that feature very high solar absorptance with a low emittance that reduces re-radiation losses from the receiver, overall resulting in an exceptional efficiency for Gen3 systems. We have since subjected the coatings to several rounds of independent testing on sun at Sandia National Laboratories and the National Laboratory of the Rockies (previously, NREL). The coatings continue to amaze us by retaining their excellent optical properties with flying colors—or in spectral parlance, “flying wavelengths”—under on-sun conditions.

Aside from the surface sciences and engineering, the research projects in my laboratory include grid integration of solar energy, solar forecasting under uncertainty, and thermal and thermochemical energy storage.

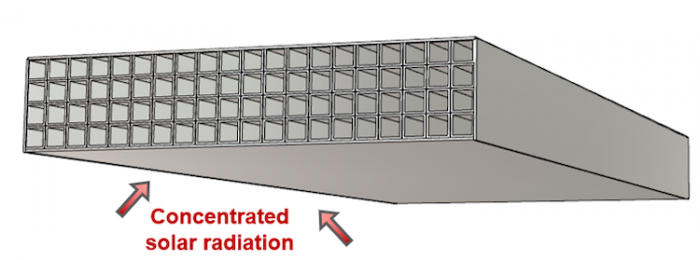

SK: I’ll add the links to these when I post this. And your papers (below) advance particle-based heat exchangers for CSP. What are the unique challenges in designing heat exchangers for a falling particle system?

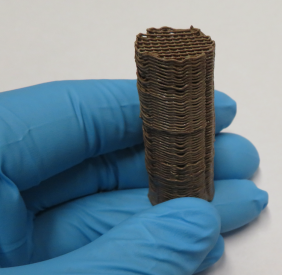

RP: One of the things that’s unique about particles, as opposed to the other fluids, is that when they interact with the surfaces on which they move, they introduce a different type of degradation than, say, molten salts and others. And this is really pertaining to the wear on the materials as particles interact with the surfaces. There are two ways that particles interact with a surface. One is when particles impinge on the surface and cause what’s called erosion, or erosive wear. The other is when a bed of particles slide on the surface, and they create what’s called abrasive wear. At high temperatures there’s also oxidation happening on the surfaces at the same time, that gets vigorous as temperature increases. All of these mechanisms occurring simultaneously need to be understood to predict how materials that interact with the particles may degrade or lose mass over time.

SK: Can you adapt abrasion lessons from other industries or are they too different to CSP?

RP: There’s a whole field – tribology – focused on wear mechanisms, but they were focused on particles interactions at low temperatures, room temperature or slightly higher, not at the temperatures that we see and expect to see in next generation CSP. So, there are unique challenges to abrasion in high temperature CSP, and there was a science gap that existed when we started looking at this problem. The question is how the interactions of particles, maybe carbo beads or silica sand, with the various components of the falling particle, CSP system influence material degradation at high temperatures.

A lot of work has been done on the solar receiver component. But there is a whole slew of other components. How the particles interact with the transfer chutes, with the valves and storage bins, and with the surfaces in the heat exchanger? So that’s kind of how we got interested in this problem; finding the wear mechanisms and the wear behavior of the surfaces, as particles are interacting with the various sub-components of the CSP system.

SK: How do you simultaneously maximize heat transfer and minimize abrasion?

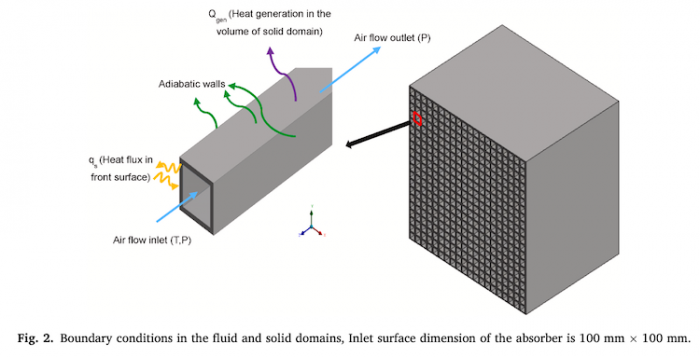

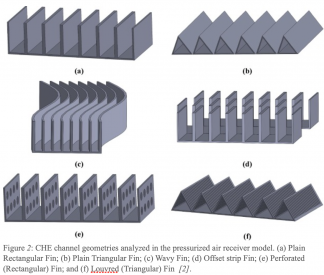

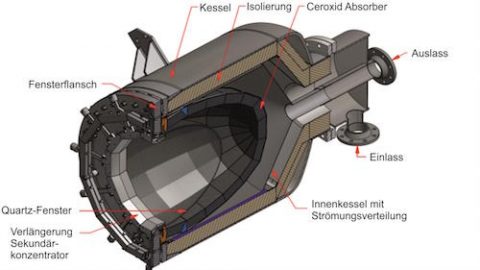

RP: We studied the particle s-CO2 shell and tube heat exchanger configuration, and quantified both the heat transfer performance and the surface wear simultaneously. This is the first study of its kind looking at the two aspects together. The study brings forth the tradeoffs: designs and conditions that provide for good heat transfer are not necessarily the ones that are benign to erosion or abrasion wear. For example, you may want close packing of the heat transfer surfaces between which particles flow, as that would be good for heat transfer, but that’s also terrible for abrasion, because the particles are trying to squeeze in through the narrow gaps between surfaces, and rub against the surface and abrade more. The question then is, how do we develop designs that trade off between these physical mechanisms through fundamentally understanding the mechanisms.

To answer the question, we studied the heat transfer and abrasion characteristics quite comprehensively and developed trade-off maps so that designers can select tube layouts that achieve the desired heat transfer while keeping abrasion within whatever their desired limit is. What makes this a first is the coupled thermal and abrasion study for heat exchangers. Heat exchanger analysis is well established and can be found in textbooks, but they are based on fluids, liquids and gases flowing through the passages of the heat exchanger. Abrasion and erosion are at the heart of the field of tribology, but its confluence with fundamental heat transfer analysis, heat exchanger analysis, and in the context of a particle medium, is where the gaps, challenges and opportunities are. Our studies are filling this gap for the engineering community.

SK: So as Gen-3 CSP develops you want to clear any issues in advance?

RP: Right. We are trying to engineer this system without a full understanding of the science behind it. That’s really where our work comes in. We want to put out the science so that anybody can use it, and we make it in a way so that it’s not solving just one problem, but we give a design map that anybody can use for their material, for their system, and so forth.

SK: Which metal is it?

RP: We are studying different alloys, stainless steel, Inconel alloys, Haynes, and ceramics such as silicon carbide, to name a few. And usually the wear rate is a function of material properties such as hardness. So, we try to present results in a general form so that the results can be translated across materials.

SK: Could you make a harder metal?

RP: Yes that’s a whole field in metallurgy, how do you harden surfaces and materials? The other way to harden materials, and make them immune to abrasive or erosive wear, is with coatings. With a carbide coating, for example, you can bump up the surface hardness by a factor of five, ten, or more. Correspondingly, the wear rate can be diminished by about that factor. But then the question is, what is the cost trade-off? Is the cost of coatings worth the reduction they provide, or can we alter the heat exchanger design or its configuration, so that we may not need this coating, but can still reduce the wear? Another factor that comes into play are the oxides that grow on the surface at high temperatures, which may be beneficial in reducing wear, depending on the competing rates of oxidation and abrasion or erosion. Understanding all of these considerations is the crux of cost-effective and viable engineering for particle-based Gen3 CSP.

SK: Might this happy medium negate the potential advantage of using high temperature particles and s-CO2 cycle?

RP: The idea is not to degrade performance. Heat transfer is often the most important part of the thermal system. But within a desired heat transfer range, what is the abrasion or erosion wear for those designs? Then if I tweak the heat exchanger performance a little bit, am I saving a lot on material wear? So you can do the tradeoffs of heat exchanger efficiency – giving up a little bit on the efficiency – if that amounts to considerable increase in component life. Or you may say, material wear is paramount. If you want the material wear to be less than say 10 microns a year, you can determine the upper bound on the heat exchanger performance for this constraint. Either way it’s information for the designer to say, which way should I go? Our experiments and modeling are aimed toward developing happens when the particles interact with the surfaces at high temperatures in a heat exchanger and in other components.

SK: Right. Gen-3 particle CSP has such high temperatures, even up to 1500°C.

RP: As I mentioned before, one of the consequences of the high temperatures is oxidation. The surface grows an oxide layer, and so the particles are now interacting not with the nascent surface, but with the oxide layer on top. Now, there are many fundamental questions. What does the oxide layer do? Does it help to kind of shield the underlying surface from the particles? Does it make it worse? Does it crack and go away, all kinds of things can happen. So we are deliberately uncovering the physics of what happens at high temperatures to the layers. And it is fun part to be working on the problem, both from an experimental side and the computational modeling side. We have very detailed experimental data and very insightful simulations of the oxide layer growth with simultaneous abrasion that explain the data, which we’ll publish soon.

It’s a really fantastic domain of problems. We’re marching along trying to understand as we go and at the end we’ll have really nice portfolio of science that we have discovered, but also solutions enabled by the science. The more we approach the problem with a systematic focus, rather than a hurried “let’s put it together and see” approach, the more we can make advances towards the final goal of achieving cost competitive CSP. CSP is an awesome technology, perhaps less appreciated, whether it generates firm power or heat. And heat – generated cleanly – is very, very important for many applications.

SK: So if you were to predict the future, would you say that particle CSP with the s-CO2 Brayton loop is the future? That tiny little turbine is really a big, major change. I remember seeing the turbine at Crescent Dunes, it was like a 747. How could you make cheap power with something that gigantic?

RP: The large power block that you saw is similar to that in fossil powered plants that use steam for power generation. Steam cycles are at their limit of efficiency and pushing the efficiency higher quickly becomes cost prohibitive. s-CO2 based Brayton cycle offers the efficiencies needed for cost-competitive CSP. The genesis of a concerted development of s-CO2 cycle components, the tiny turbines, the compressors, and other subsystems dates back to SunShot. Since then a lot of progress has been made in addressing challenges in terms of materials, being able to handle the high pressures and so forth, and we are advancing closer to viable commercial system. And since a power block is something that is shared with conventional power generation, it really benefits multiple technologies: fossil and nuclear in addition to solar thermal. In reality, the first adopters could be fossil because there’s so many of them.

SK: But why should the fossil industry get to benefit from all the work done by concentrated solar researchers?

RP: That’s one way to see it. I actually see it a different way. If you can reduce the cost of the power block through the larger deployment opportunities in fossil or nuclear, that ultimately benefits CSP. So the more the deployment opportunities in other thermal plants, the more CSP benefits from that lower price. What SunShot brought was a sense of purpose, direction and urgency, in terms of what we need to reach the efficiency target for CSP, and what does the s-CO2 cycle have to look like? Without a purpose, if you just say, oh, this cycle looks like a good idea, let’s just explore, and see what we can develop – then you don’t know where you’re going, or how far you need to go. And all that changed with the DOE Gen-3 solar program that pushed for the s-CO2 Brayton cycle with particles for heat transfer.

Papers:

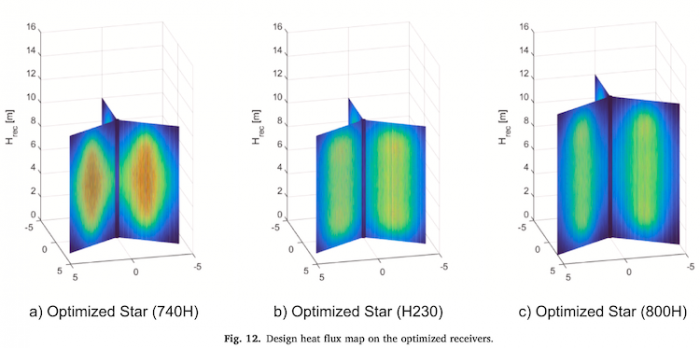

Analysis and design of a particle heat exchanger for falling particle concentrating solar power

Analysis and mitigation of erosion wear of transfer ducts in a falling particle CSP system

Analysis of erosion of surfaces in falling particle concentrating solar power