IMAGE © Maria José Montes: Compact Solar Receivers: Emerging Opportunities for Industrial Heat Processes The FLT20 linear Fresnel collector developed by SOLATOM

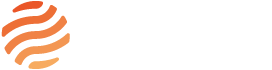

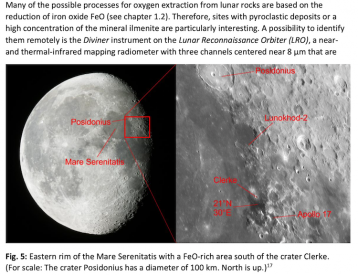

The background

For decades, gases have been largely overlooked as heat-transfer fluids in concentrated solar receiver systems, mainly due to their poor heat transfer capability and the high pumping power required.

Early research on gaseous heat transfer fluids in solar receivers relied on air at atmospheric pressure in volumetric receivers. Although technically feasible, these systems did not achieve sufficient heat-transfer performance to justify their complexity. And the extra power needed to circulate low-density gases reduced overall efficiency.

In recent years, research attention has shifted toward very highly pressurized gases like supercritical CO2 – which are considered to be actually fluids at these high pressures – approximately 200 bar.

These liquid-like densities and improved heat-transfer characteristics have made supercritical CO2 attractive for high-temperature applications. However, such systems require powerful compressors, thick-walled components and stringent safety measures, which increase technical complexity and capital costs.

These two historical pathways leave open an important question: is there a technically and economically viable intermediate solution?

An intermediate pathway: moderate pressures, modern design

As Professor at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), María José Montes proposes revisiting moderately pressurised gases from a new perspective. Rather than focusing solely on fluid properties, her approach, with support from the BBVA Foundation’s Leonardo Scholarship for Researchers and Cultural Creators 2024, re-examines the interaction between fluid behaviour and receiver geometry.

The idea of using pressurized gases is not new in her research trajectory. Early in her career, while working at CIEMAT in a research project led by Nobel Laureate Carlo Rubbia, a prototype pressurized-gas loop was constructed at Plataforma Solar de Almeria (PSA), for parabolic Trough collectors.

“Although the project operated correctly, it did not provide a sufficiently strong competitive advantage to justify the use of pressurized gas in parabolic Trough systems,” Montes explained in a call from Spain.

“The absorber tubes were designed for liquids and were not cooled as effectively when the heat transfer fluid was a gas. Gas leakages were detected in the ball joints connecting the receivers to the stationary piping. This technological constraint limited the practical viability of pressurized-gas operation in Trough plants.”

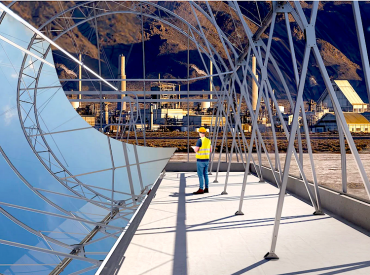

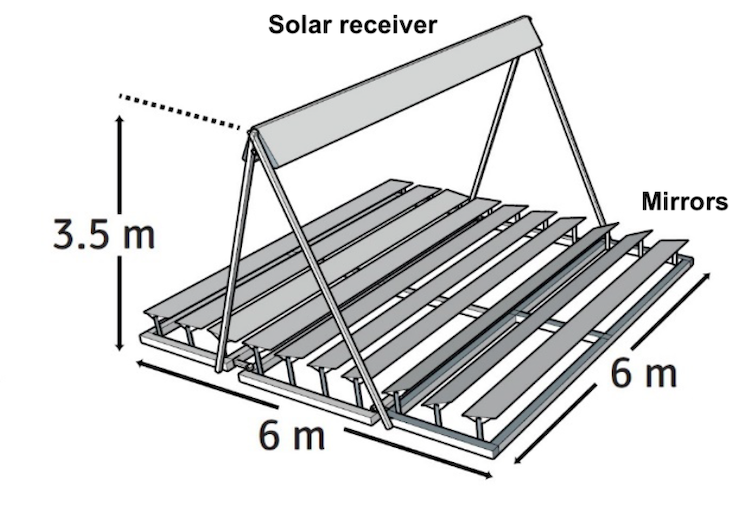

But Linear Fresnel has a different configuration than Trough. The mirrors on the ground track the sun’s movement and the system integration is simpler. Both the receiver and the heat-transfer piping are stationary, so with no rotating joints there’s no leak risk with gases.

IMAGE © Maria José Montes: Compact Solar Receivers: Emerging Opportunities for Industrial Heat Processes The FLT20 linear Fresnel collector developed by SOLATOM

Because of this difference, Montes has now proposed taking a new look at combining Fresnel with a new compact reciever designed for gas for the heat transfer.

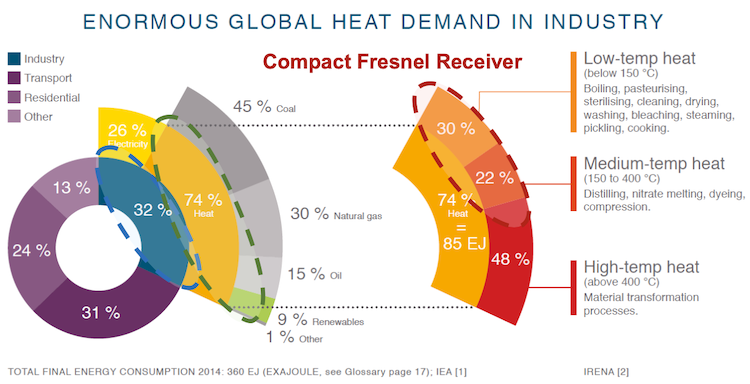

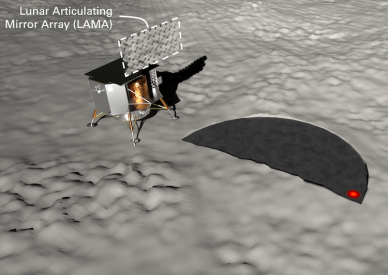

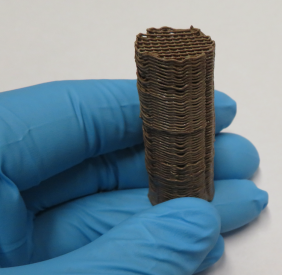

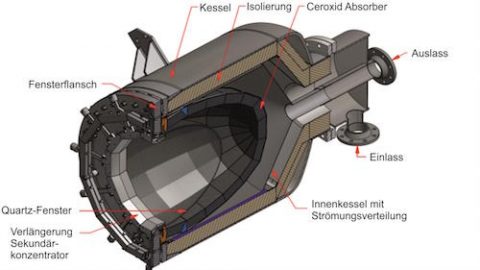

IMAGE © Maria José Montes: Compact Solar Receivers: Emerging Opportunities for Industrial Heat Processes – instead of the glass tube in traditional Frenel receiver, the new design is a solid block of metal with channels for gas to flow through

Fresnel with a new solar receiver designed for gas

Traditional Fresnel solar receivers have cylindrical glass tubes optimized for high-density fluids, but they are not ideal for gases, whose lower density and heat capacity require different flow and heat-transfer characteristics.

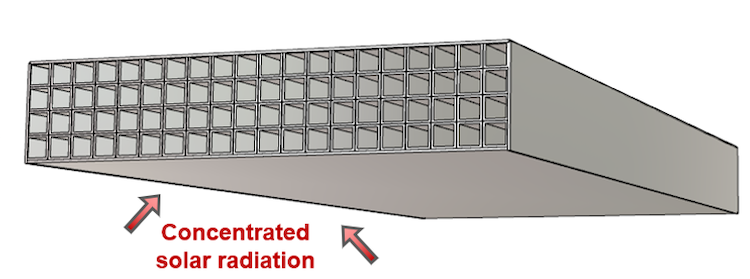

Montes team designed a compact solar receiver made of a CuCrZr copper alloy, a material widely used in high-performance industrial applications due to its excellent thermal conductivity and mechanical strength.

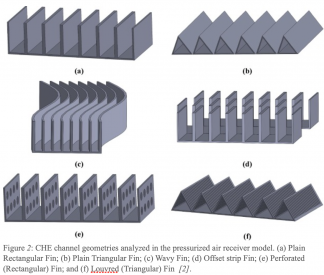

The compact receiver consists of a finned core with internal channels through which the gas flows, maximising the heat transfer surface area. This increased area compensates for the inherently lower convective coefficients associated with gaseous fluids.

What their modeling showed

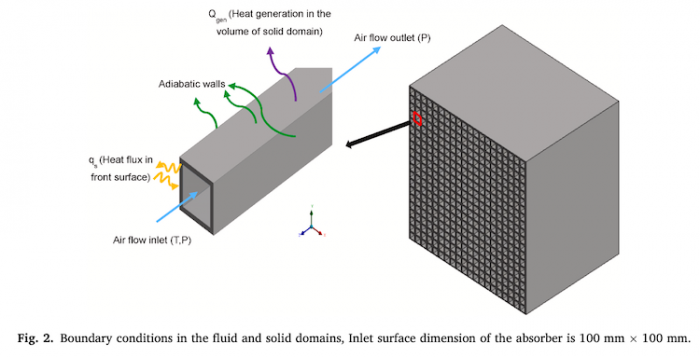

Using a commercially available Fresnel module from Solatom the team evaluated different internal configurations of the absorber block.

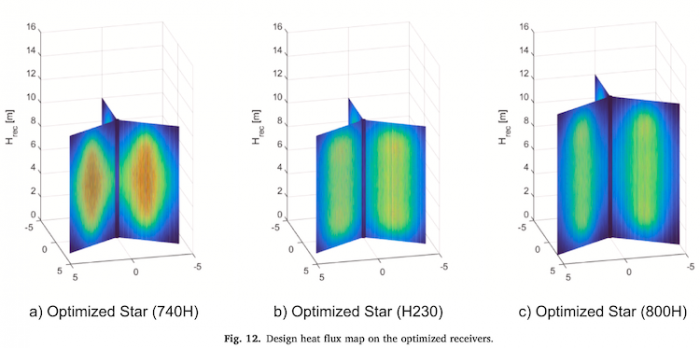

The study examined inlet pressures between 5 and 30 bar, two to four rows of internal channels, with widths between 6 and 16 cm, variations in aperture width and tube diameters for three possible gases, N2. He and CO2.

The team assessed the performance in terms of useful heat gain, pressure drop, energy efficiency and exergy efficiency. The results are diagrammed in a SolarPACES conference presentation (Compact Solar Receivers: Emerging Opportunities for Industrial Heat Processes).

The modelling revealed that all three gases delivered comparable useful heat and overall energy efficiency. However, there were differences in pressure losses and blower power requirements. At equivalent pressures, CO2 achieved the highest exergy efficiency and required the lowest blower power.

Increasing inlet pressure improved both heat transfer and system behaviour up to around 10–15 bar. Beyond this range, energy and exergy efficiencies tended to level off, as improvements in heat transfer were offset by higher compression work.

Pressures within this range are suited to many industrial steam applications, which typically operate at 8–9 bar, making this a very practical technology for supplying industrial heat.

Montes’ recent work, published in Applied Thermal Engineering. “Towards a General Design Framework for External Tubular Solar Receivers Using Pressurized Gaseous or Supercritical Fluids” explored two key findings; the suitability of CO2 as the most promising pressurized gas at intermediate pressures and the identification of a threshold operating pressure. The study had similar findings for central receiver systems for electricity production.

A “Goldilocks” solution for industrial heat

The advantages of pressurized gases are that they are non-corrosive, non-toxic and thermally stable over wide temperature ranges. When combined with a geometry optimized for gas flow, the proposed solar receiver design enabled higher heat-production capacity, reduced absorber area, lower thermal losses, smaller solar fields and thus potential capital cost reduction.

Because electric grids are increasingly renewable, industrial heat supply is the next area of research for concentrated solar technologies, because its direct heat has been shown to be lower cost than running using electricity to produce heat, particularly in the low-to-medium temperature range of many industrial processes.

While Tower systems currently dominate solar power generation due to their high efficiency at very high temperatures, Fresnel systems offer advantages for industrial heat, with their compact layout, low cost and simple integration.

Next: experimental validation on-sun

The team had done lab scale tests at IMDEA-Energy, through the ACES4NET0 project, funded by Comunidad de Madrid through Tecnologías 2024. The next step is validation on-sun under real operating conditions in a Fresnel test loop running with pressurized gases. The conventional glass-tube receiver will be replaced by the new compact absorber, and the Fresnel loop will be adapted to run on CO2 gas.

Industries are showing interest, and further development could lead to national or European-scale demonstration projects.

Montes team’s second look at moderately pressurized gases enabled by their design of a novel Fresnel gas receiver has opened a new pathway for efficient, cost-effective solar heat for industry. Stay tuned…

Finding an ideal channel geometry inside compact flow gas receivers

Optimizing the safety factor in high temperature solar absorbers