Solar calcination + sCO2 cycle

In a year-round California-based study, a Chilean research team has continued to advance a potentially more cost-effective and efficient form of Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) that leverages limestone’s heat generation during calcination.

In this new solar tower form of CSP, the solar receiver in the tower acts as a calciner, and thermochemical energy storage feeds a supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle in the power block (instead of today’s commercial tower CSP that pairs molten salts storage with a Rankine cycle power block, which has temperature limitations).

This concept is among those being researched for Gen-3 solar towers due to the potential for greater efficiency and lower costs from a higher-temperature operation.

In their study, Annual performance of a calcium looping thermochemical energy storage with sCO2 Brayton cycle in a solar power tower published at Energy, the Chilean team ran dynamic TMY-based simulation with hourly solar variability, for a year.

High temperature operation for the s-CO2 cycle

The process would be more efficient than today’s CSP, as it can operate at higher temperatures, between 700°C and 1000°C.

“There is a synergy between the calcium looping process and the sCO2 Brayton cycle,” explained lead author Freddy Nieto, in a call from Santiago.

“There is a specific relationship between them, because the reaction temperatures in the calcium carbonate system are higher than 550 °C. We can reach up to 865 °C, which leads to higher efficiency in the power block—the supercritical CO₂ Brayton cycle. By using this thermochemical energy storage system, we are able to operate at higher temperatures and therefore use a higher-temperature power block than in a Rankine cycle. For this reason, there is a strong synergy in the operating temperature between both systems.

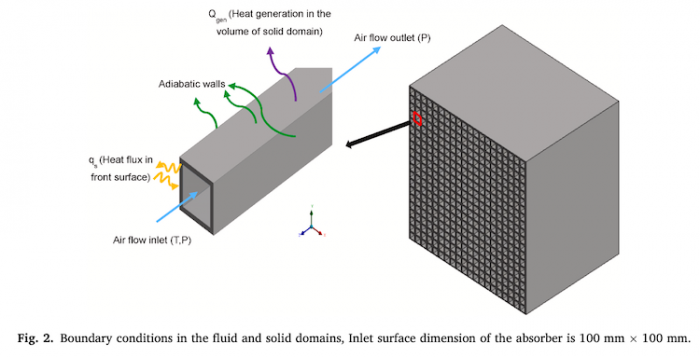

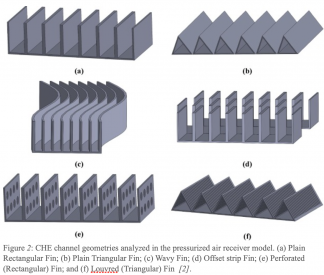

The study dynamically models and controls the solar field, the calciner/solar receiver, the carbonator, both storage silos, a CO2 vessel, and the sCO2 power block, together, based on a theoretical 100 MW tower project at the California site of the original trough CSP projects.

“We based our study on the DNI at that particular site in the USA,“ Nieto noted.

“We are using a program called OpenModelica, which allows us to solve the differential equations that describe the mass and energy balances of the plant. This represents a key difference compared with previous studies based only on static simulations. In our work, the dynamic annual simulation provides the full differential equation system internally and solves it over time. As a result, we can capture not only the plant’s operational behavior, but also its response to the dynamic variations in DNI throughout the entire year.”

How a solar calciner enables a new kind of tower CSP

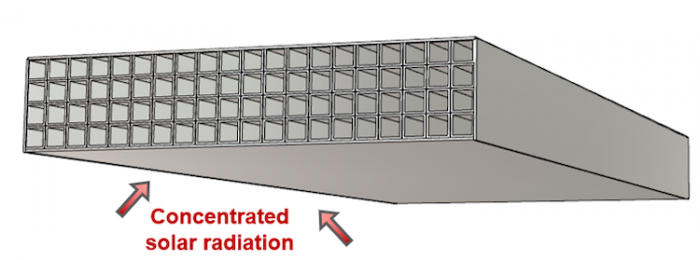

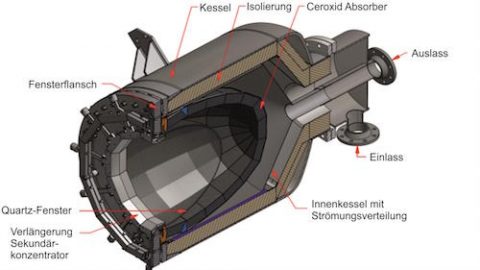

Instead of using a solar receiver to heat liquid molten salts that would then store the heat thermally, as in today’s tower projects, the solar receiver serves as a calciner, converting limestone (CaCO3) into quicklime (CaO) and carbon dioxide (CO2) at 850–950°C.

The quicklime would be stored in silos, and the CO2 gas would be stored in a pressure vessel; each can remain inert and ready for days in separate storage.

Then, when electricity is needed, the quicklime and carbon dioxide would be reacted together in a carbonator, releasing heat at around 750–865°C which is supplied to the power block to drive the very efficient sCO₂ Brayton cycle.

The plant would switch between charging (calcination) and discharging (carbonation) modes, with automated control managing solar input, material flow, and energy dispatch. It includes mechanisms to defocus the solar field and bypass compressors in order to reduce parasitic losses.

Because the storage is thermochemical, the solar field configuration differs from a typical tower project today.

In today’s commercial tower CSP plants, the solar receivers are heated from all sides at the center of a surround solar field layout. These operate at a temperature sufficient to run a Rankine cycle, about 450°C.

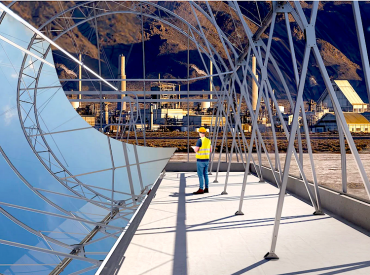

However, for higher optical efficiency, in order to operate at a higher temperature for this calcining action in the receiver to feed this thermochemical form of storage, cavity receivers are employed together with a polar field heliostat layout.

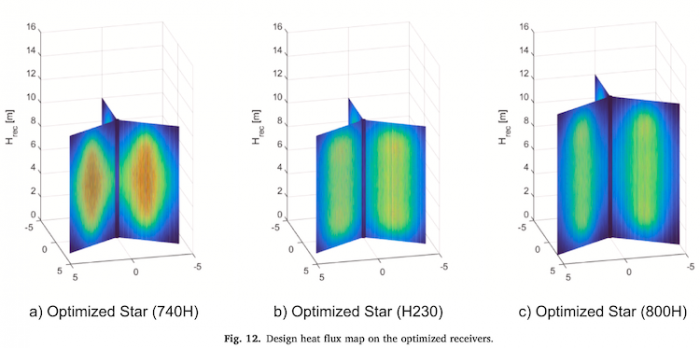

This tower would host three cavity receivers, each with a 180° acceptance angle. The three heliostat fields of mirrors would be concentrated in each angular sector where the cavities “see” reflected sunlight, reducing the number of required heliostats for the fixed projected thermal input.

Material handling – limestone

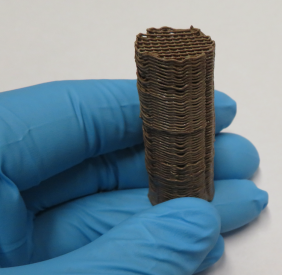

Limestone is abundant and inexpensive at $10 a ton (molten salt is ~$800 a ton) and has a chemical energy density of around 3.2 GJ per cubic meter.

Learning from research in other particle-based CSP, like Sandia’s pilot project, a screw conveyor and a hopper like in the mining industry would be used to carry the stored limestone from the silo up to the calciner in the tower.

“So we move it with conveyors to the top of the tower, to the entrance of the reactor, where we need the homogeneous distribution of the material to have the best CaCO3 conversion reaction in the calciner,” Nieto explained.

But as with the other Gen-3 particle-based CSP technologies (such as those that use bauxite sand to convey and store heat), there are unique challenges with using a powdery particle like limestone.

“Material sintering does impact its reusability,” he noted.

“The cyclability is reduced by some percentage in the conversion reaction in the carbonator after each cycle. So, for example, at the beginning, we can start with a 70% conversion reaction, but after 100 cycles, it can drop to a 30% conversion reaction. To solve that, a make-up/purge subsystem can be implemented, so that it can refill what you lose each cycle.”

Results of a solar tower calciner with the sCO2 cycle

They compared their proposed system of a solar tower calciner paired with the sCO2 cycle against both a “base case”- today’s tower with molten salt storage and Rankine cycle power block, as well as to a sort of hybrid: a calcium-looping thermochemical energy storage plant, but still connected to a Rankine cycle.

They assessed annual net generation, solar-to-electric and dynamic plant efficiency, capacity factor, and LCOE for all three systems.

Even with new parasitic loads, such as solids transport and CO2 compression, and a CO2 bypass that reduces compressor work in defocus mode, the calcium looping sCO2 system with a Brayton cycle delivered the highest efficiency, reaching about 34–40% dynamic efficiency, versus roughly 27–33% for the molten-salt reference.

Design parameters like solar multiple, concentration factor, and storage size interact strongly.

For example, they found that under similar conditions, if the solar multiple is 2.6 rather than the 2.1 of a typical tower project, and if the storage is enough to deliver for 24 hours, the LCOE for California is reduced to below 110 USD/MWh, compared to 118 USD/MWh for the base case.

(For perspective, in California, the LCOE of PV and battery systems fall between $50/MWh and $131/MWh.)

A solar sulphur cycle to make unlimited thermal energy storage

Solar-heated cement calcining – aided by the greenhouse gas effect?

Thermochemical energy storage to deliver Gen3 solar 365 days/yr