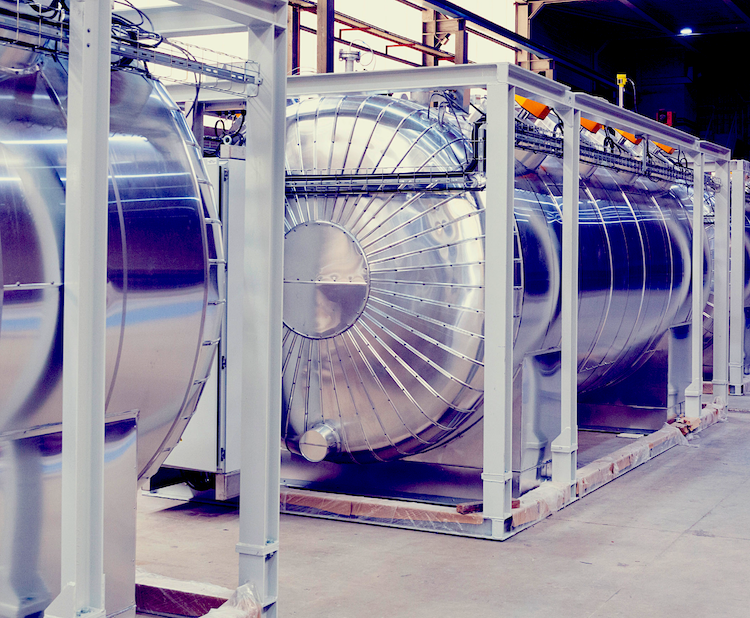

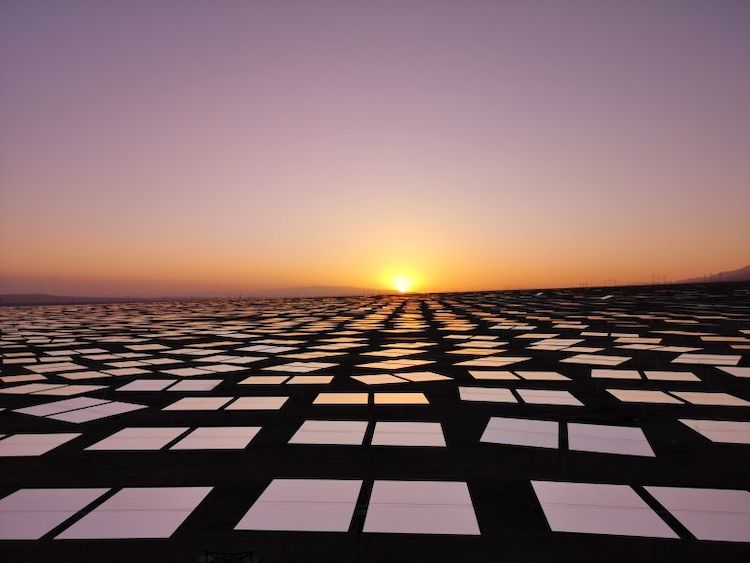

Spain’s Gemasolar, the world’s first utility-scale tower CSP with storage for all night operation IMAGE@Wikipedia

The time is right to consider what went wrong and what went right with Spain’s previous CSP policy – because an election in June put the renewable-friendly coalition that developed it back in power.

Spain’s socialist-led coalition government jumpstarted virtually all the Concentrated Solar Power/CSP deployed in Europe, 2.3 GW, creating a supply chain of Spanish CSP companies that now lead the industry globally.

Then in 2010, some cost-cutting regulations were instituted in Spain, after the international financial crisis of 2009 that hit many countries hard, reducing electricity demand and exacerbating Spain’s oversupply problem. In 2011 the conservative Partido Popular took power, joining with Poland and other “climate laggard” nations blocking clean energy initiatives.

In 2012, the conservative Rajoy-led government placed a complete moratorium on making any more payments on existing contracts with already operating CSP plants, resulting in bankruptcies and lawsuits, and bringing the burgeoning industry to a halt.

However, in June, the conservative government was ousted and a new socialist coalition was returned to power, headed by Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, that is expected to be much more renewable-friendly.

Pablo Del Rio, Senior Researcher at the National Research Council of Spain (CSIC:

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas) pointed to an indication that the new government is more likely to understand the value of CSP in transitioning from the old base load power grid to a flexible grid that supports the intermittent renewables; PV and wind.

“There is this dedicated transition ministry. A Ministry for the Ecological Transition has been created. Before, the energy responsibilities were in the Ministry of Industry. This is a feeling, but that is kind of telling you a little bit about the importance given to the low-carbon energy transition, so if I were in the CSP business I would look at Spain now with a little bit more optimism now,” he said.

Alluding to the economic recovery in part, he added: “Although we should be cautious, there are reasons for optimism that they will be more favorable than the previous government towards renewables in general.”

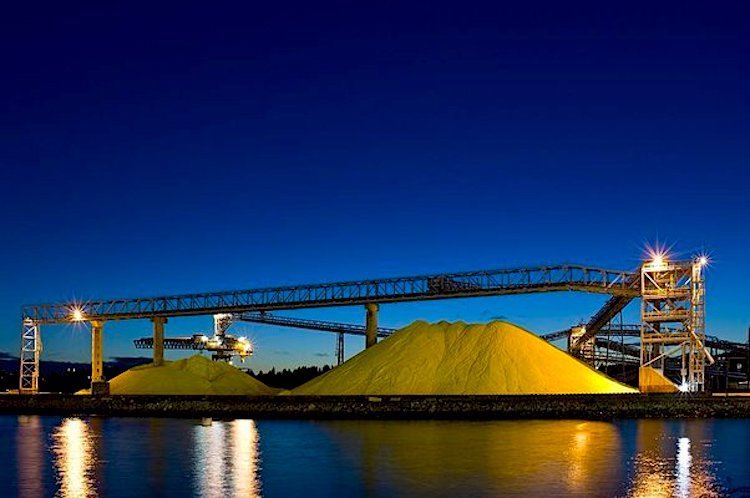

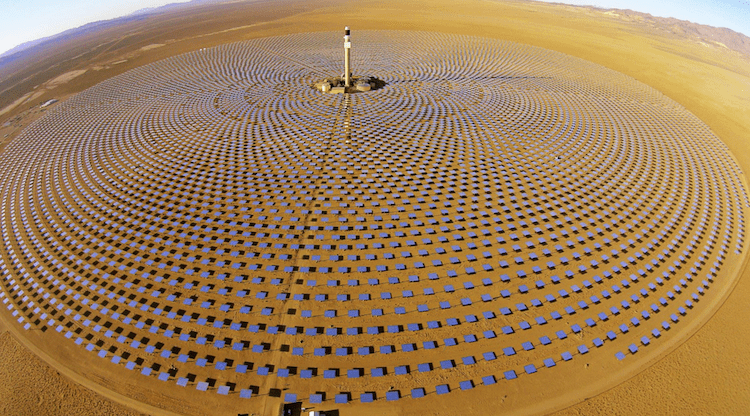

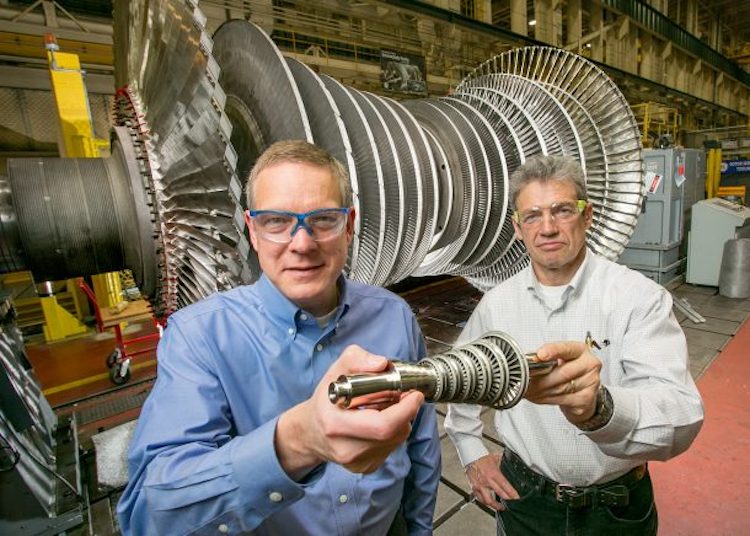

CSP is a much more localized and industrialized solar technology than PV. IMAGE@NREL

Spain’s new government could take another look at the value of CSP, not just for its ability to provide dispatchable solar when needed, making it the flexible foil needed in a high renewable environment, but at its likelihood of fostering a new industrial sector in Spain. CSP is a much more localized and industrialized solar technology than PV.

“With PV you basically just import the panels from China. But with CSP we create a local industry with local jobs in a developed country which is not highly industrialized,” he said.

How to improve Spanish CSP policy

Del Rio is the author of Analysis of the Drivers and Barriers t the Market Uptake of CSP in the EU published at Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, and at MUSTEC and has worked on renewable policy for more than 20 years.

For his paper, Del Rio interviewed 11 key stakeholders (industry and research centers) from the first round of Spain’s CSP development to define those drivers and barriers.

One policy that all agreed was a major driver was Spain’s Feed-in Tariff (FiT).His view is that the FiT was the appropriate instrument to kickstart the completely new industry of CSP in its initial stages, but that it should have been staggered annually and reduced in predictable stages in both amount and capacity as more gets deployed.

“I like Feed-in Tariffs for the initial stages of a technology. But a capacity cap and a degression mechanism should have been put there,” he said.

“We had that for PV, although too late, since 2008; it had this gradual rate degression, whereas the support provided would depend on the degree of installed capacity in the previous period. That made a lot of sense. But you have to be careful to put a cap. Maybe 500 MW for this year and then next year a gigawatt at a lower tariff and two years later, another gigawatt at an even lower tariff. You have to give investors certainty. This also sends the appropriate signals to actors throughout the whole value chain.”

Del Rio noted that some argue that Spain’s FiT resulted in too little cost reduction: “I see this point, but I also see some benefits from building that 2.3 GW of CSP in Spain. You can now see a lot of accumulated knowledge, and firms from that Spanish sector now export and they are building CSP everywhere.”

Indeed, Spanish firms do now dominate the global CSP market. Gemasolar’s SENER has built 29 CSP plants globally, from Morocco to South Africa. Acciona went on to build in the US and now, with Abengoa, is restarting Cerro Dominador in Chile. Abengoa built plants in the US and South Africa and recently cracked the promising new Chinese CSP market.

Spain will need CSP’s storage by 2030

The brief FiT was the only policy tried in Spain. None of the subsequent policies such as South Africa’s solar auctions for after dark were tried in Europe. Only CSP can generate solar at night, so these auctions were de facto CSP dedicated.

“We had nothing like that in Spain; like Dubai where they are required to produce electricity from 4 PM to 10 AM” he said.

Although Spain held dedicated PV or wind auctions: in January 2016 for wind or biomass, for all technologies in May 2017 and in July 2017 for wind and PV, there have been no dedicated auctions for CSP. As elsewhere, PV costs have plummeted fast, and Spain has seen rapid growth of PV, since 2007 to 2009, when there was just 300 MW, and nine months later it was 3,800 MW.

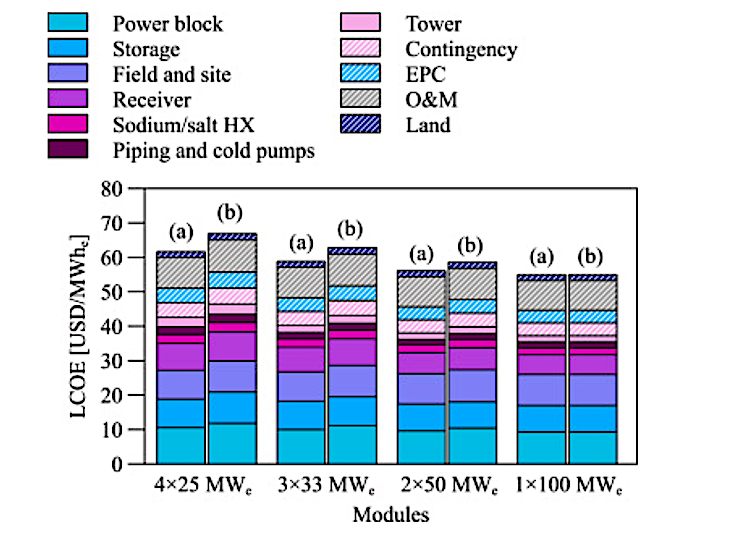

Nor were there auctions for renewable energy storage. There was a technology-neutral auction in May of 2017, but dispatchability; the ability to deliver power at any time was not an explicit pre-qualification requirement. The bids were awarded based only on the lowest LCOE and storage was not considered a necessity.

But if CSP makes a comeback, it will be in a very different power environment. For one thing, the grid is no longer the base load grid of 2006.

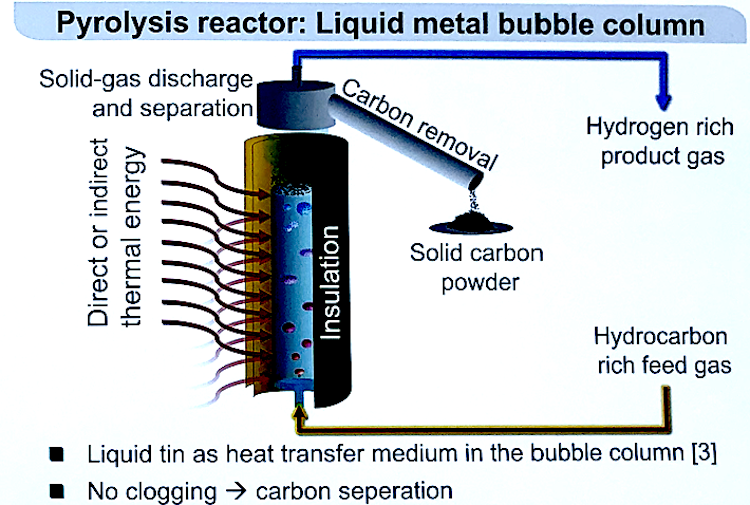

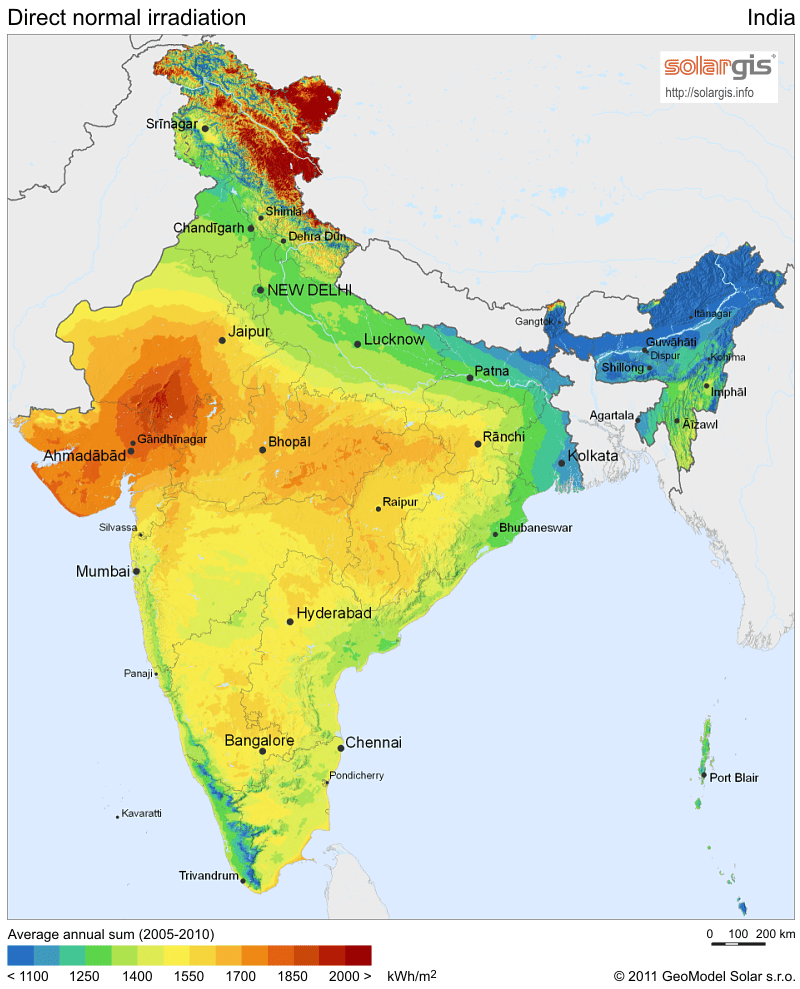

“The closer we approach 2030, the more sense CSP makes because you can store the energy to provide dispatchability. Coal is going to be phased out. There will be a huge penetration of intermittent renewables; we’ll have an additional 4 GW of PV and 4 GW of wind if the projects awarded in the tenders are built by the required date (December 2019), so you have to do something about the intermittency,” said Del Rio.

Yet, by making no plans, the fall-back for dispatchable generation would inevitably default to natural gas, yet gas must be phased out to meet Spain’s climate commitments at Paris.

Ensuring contracts are secure would cut costs to Dubai levels

In his paper, Del Rio found that the most relevant drivers were “the high technology dynamism of the sector, the significant potential for cost reductions through learning effects, the creation and consolidation of an industry and support policies can be expected to be key drivers for the future uptake of this technology.”

The barriers were “the comparatively high costs of the technology, competition with other technologies (whether renewable or not), difficulties in accessing finance, closely followed by uncertain and retroactive policies.”

“Difficulties in accessing finance” is closely connected to the “uncertain and retroactive policies.”, although it was also related to the economic and financial crisis in 2008-2013. Financing would not cost as much and prices could drop, if bankers had the certainty of a guarantee that contracts would be honored.

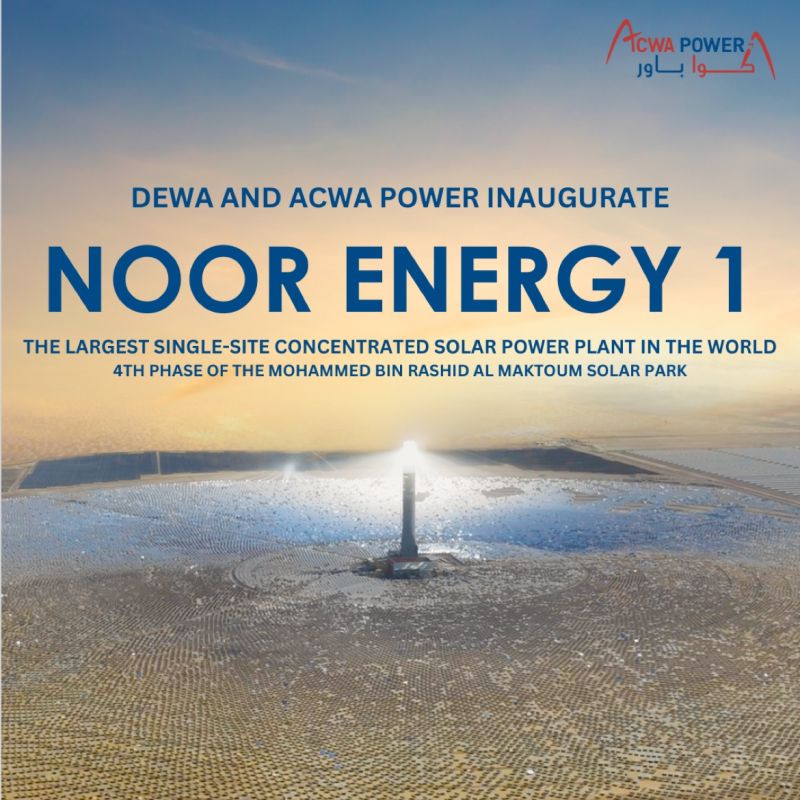

In 2017, ACWA Power was able to bid power from its 700 MW CSP project for DEWA in Dubai at just 7.3 cents per kWh, because, CEO Padmanathan noted, their financing cost was just 6%, a new low for CSP, as bankers become more comfortable with the reliability of the new technology, even though only its first 5 GW are deployed globally.

“In a recent World Bank webinar, ACWA Power CEO Paddy Padmanathan said that ‘if the financial conditions were the same in Spain as in Dubai, I can also build a power plant in Spain for the same price as the Dubai plants financed at an average rate of capital of around 5.5%’, which is the commercial rate also in Spain,” ESTELA president Luis Crespo told SolarPACES.

“In planning the fleet for the next decade or so, the Ministry should keep in mind that the backup we have today won’t be in operation by 2036. We are going to have problems with only wind and PV going ahead,” Crespo added.

Crespo noted that many commercial loan rates in Spain are similar to those in the UAE, about 5.5%.

But to get those low financing costs for CSP, Spanish bankers need to be assured of contract certainty. To foster this security, the new government would need to guarantee that new CSP contracts can not be voided by future governments.