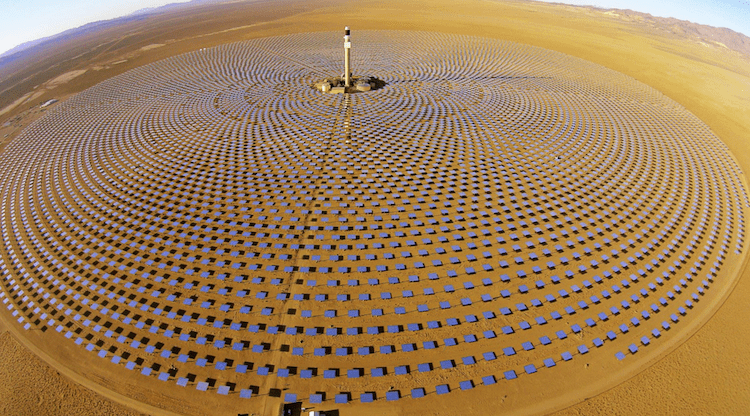

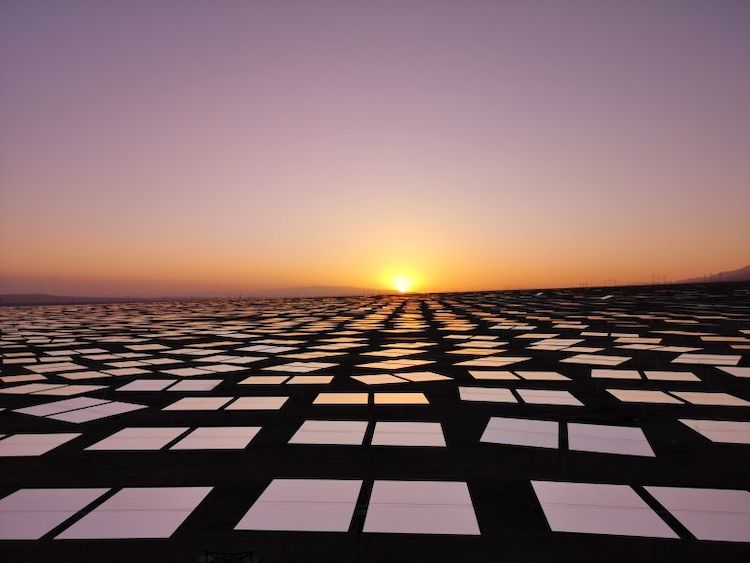

110 megawatts; CSP; Concentrated Solar Energy; Concentrated Solar Power; Crescent Dunes; NV; Solar Reserve; Tonopah; Tonopah Solar Energy; concentrated solar thermal; molten salt; storage; tower. (Jamey Stillings)

A fine art photographer can take the lions share of the credit for popularizing the “other” solar, concentrated solar power (CSP), the thermal solar technology

Images by the award-winning artist Jamey Stillings have become so widely used that it is not uncommon to see news stories about solar energy illustrated by a tower surrounded by mirrors, rather than the much more widely deployed PV.

Seven years ago, with his first flight over the site, the award-winning artist Jamey Stillings began chronicling the construction of the Ivanpah tower CSP project, as part of his series, Changing Perspectives: Energy in the American West. A few years later he added imagery of another thermal solar project, Crescent Dunes.

In the world of fine art documentary photography, Stillings had already made a name for himself with his earlier series, the Bridge at Hoover Dam, about the bridge built in the shadow of the Depression-era Hoover Dam hydroelectric project. This had already accumulated multiple awards in the international art world.

His documentation of Ivanpah continued that tradition, and a portfolio of this work was acquired by the United States Library of congress for its historical record. But what brought his work out of the world of fine art, and propelled a new visual awareness of state-of-the-art CSP technology to the general public, was this four-year series on Ivanpah, followed by an extensive documentation of Crescent Dunes; two of the five CSP projects enabled during the Obama administration.

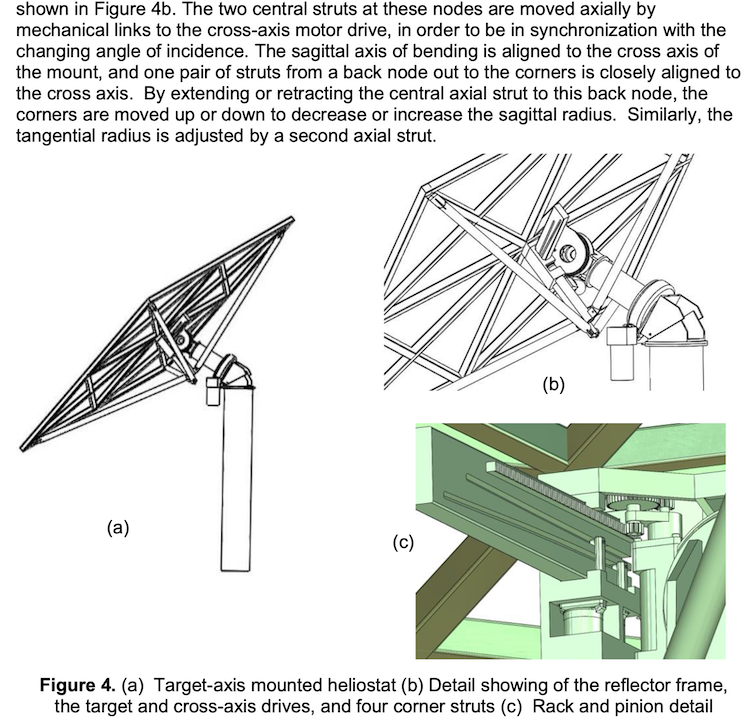

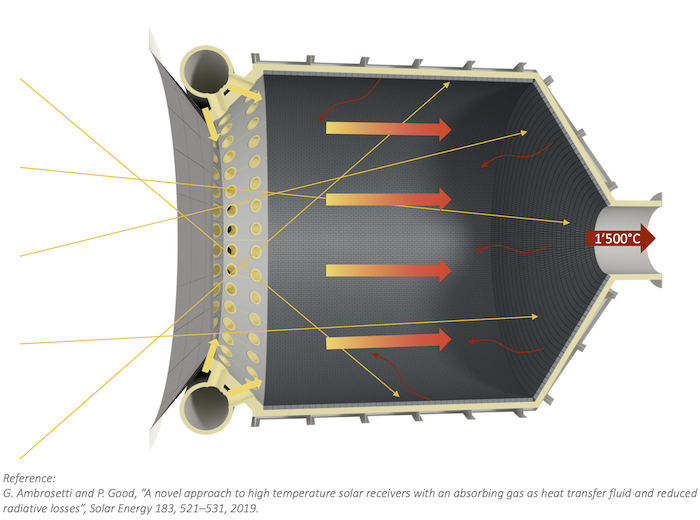

Both projects Stillings chose to document are “tower” CSP. Tower CSP is characterized by a central tower encircled by heliostats focusing sunlight on a receiver at the top, rather than by the traditional rows of trough-shaped heliostats (mirrors).

While both technologies trap and use solar heat to run a power block, tower is state-of-the-art. So there is more trough CSP installed as well as more PV. Yet ironically, now it is images of tower solar that are more often used commercially to illustrate the idea of “solar energy.”

CSP viewed from a sane energy future

In Changing Perspectives, Stillings documents the massive historic transition as humanity evolves from fossil fuels to a carbon-free energy future. He sees this evolution to a carbon-constrained future as inevitable, but like all evolution; born through duress.

“We are now at a critical juncture in the evolution of our species,” states his project introduction. “How we choose to live on Earth in the next few decades, with a rapidly growing human population and expanding consumption patterns, may determine not only our prospects for survival, but also the ultimate viability of the global ecosystem.”

The photographic record from high in the sky provides a literally “distant” and removed perspective on renewable energy development, one that suggests the inevitability of a transition to clean energy to power our future civilization. This perspective is far from the social and political turmoil and trauma that accompanies this evolutionary change.

Because the aerial images of Ivanpah are presented in black and white, the format associated with past historical records; it seems that we are dispassionately looking back at the past from some future century.

Aerial view, Solar Towers Two and Three, Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System, 4 September 2013. When complete at the end of 2013, 172,000 heliostats (344,000 pairs of garage door sized mirrors) will concentrate solar thermal energy toward three towers creating steam, which will drive turbines to produce 377 megawatts of electricity, enough to power 140,000 American homes. When fully operational, the facility will become the highest capacity concentrated solar thermal (CST) power plant in the world. IMAGE @Jamey Stillings

We seem to look back at the first truly utility-scale CSP projects from a future civilization now routinely run on renewable energy. The switch to clean energy has taken place. The evolutionary stress is now over, and a new equilibrium has been achieved. Today’s controversial switch to clean energy has become the norm.

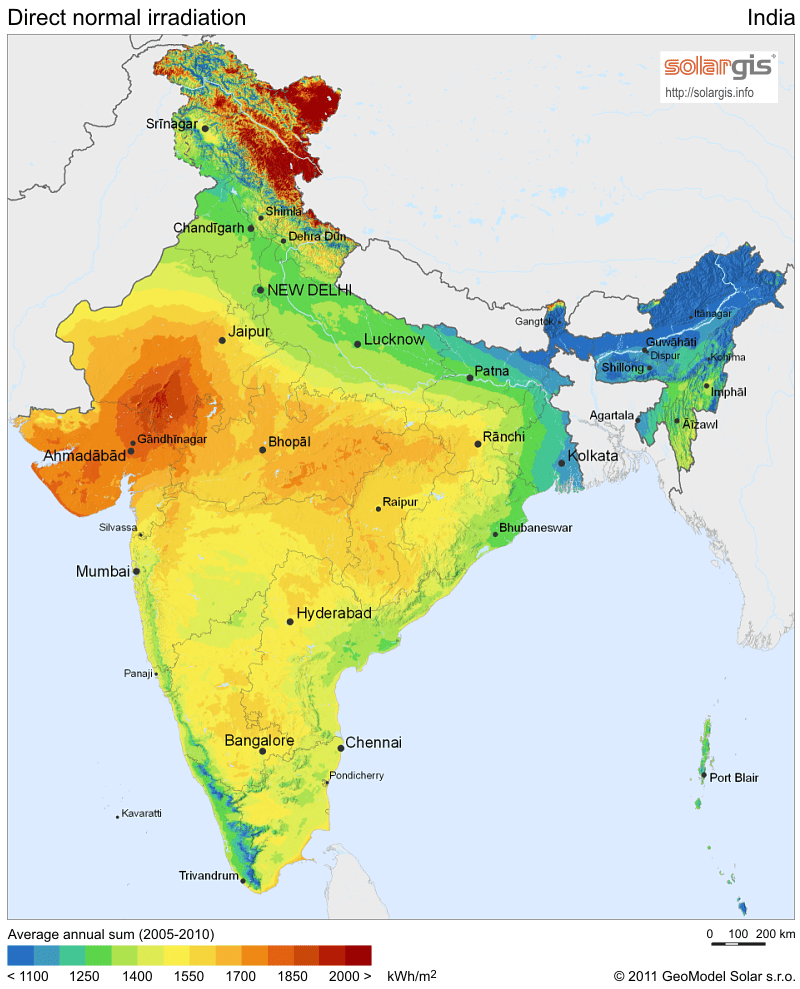

Documenting Chile’s clean energy transformation

Moving on from the US, the Stillings studio is actively searching for new groundbreaking renewable energy development internationally. Stillings will be documenting the beginnings of what promises to be massive solar deployment in Chile, a nation that he sees as the next frontier in the clean energy transition.

Next month, he begins aerial photography above a few regions of northern Chile, where mining and renewable energy share the terrain. His team is also researching China and Morocco, but with logistic and administrative challenges in these countries, Chile is the current focus.

“Last August, we commissioned a production company in Santiago to pull together research on Chile for us, which they did very well. We have been pouring over Google Earth looking at a variety of mining operations and Chilean renewable energy projects,” Stillings told SolarPACES in a call from his New Mexico studio.

“Our focus will be on the intersection of renewable energy and mining in the regions of Tarapacá, Antofagasta, and Atacama. We are becoming more familiar with the geography and geology of northern Chile. In particular, I’m interested in the symbiosis between renewable energy projects and traditional resource mining, such as copper.”

The main area the team is studying is Antofagasta; an area with a large concentration of mines. The studio uses satellite imagery to locate sites under development, shifting between the less-frequently-updated Google Earth, and satellite photo services such as ArcGIS and Terra Server, which provide more current imagery.

Art creates a new paradigm

Unlike much fine art photography; Stillings’ images have been widely disseminated internationally. His images of tower CSP have been published, many times in multi-page photo-essays, in The New York Times Magazine, National Geographic, Smithsonian, New Scientist, Der Spiegel, Le Monde, Neue Energie, and WIred Italia – to name a few.

As these images have entered the public consciousness, a surprising shift has occurred. Now it is actually more likely that a state-of-the-art tower CSP project is selected to express the concept of a big solar project, rather than the more commercially developed PV.

When this writer suggested to Stillings that due to his work with tower CSP; the least-commercially-deployed solar technology has perhaps become the default image of utility-scale solar, he chuckled.

“I don’t think I will take credit for that,” he said. “It’s nice to be published, but I’m primarily interested in informing. My goal is to inform people so they better understand renewable energy and motivate them to think about how it can apply in their particular community.”

A necessary education

With a dearth of coverage of clean energy in the broader media environment, he has found that there continues to be widespread ignorance about solar technologies, that extends to mainstream news reporting.

“I’ve spent quite some time working to educate The New York Times and a multitude of other publications featuring my work that CSP and PV are not the same. I’ve been working on this since 2012,” Stillings revealed. “Every time I chat with a new writer, they have just as much of a problem as the previous one. Whether the story is about Ivanpah or Crescent Dunes or some other project, I usually must start at the most basic level: “No, this is not a solar PV panel, this involves a mirror or a heliostat” and I’d run them through the process every time.”

But Stillings is delighted by his developing “side gig” in renewable energy education. “This photography is being seen in very diverse communities and countries, places that may have had little exposure to renewable energy,” he said. “These are very diverse communities; from architectural, science, environmental, technology and news magazines, to a wide range of daily newspapers. So it is very satisfying to see the work move out in different ways.”

“Right now we find ourselves impotent because we are unable to reach compromise,” he added. “The way our society and politics are set up right now encourages polarization and conflict rather than encouraging finding solutions and consensus. So that’s what I’m interested in. I want to my work to inform, and then to encourage more constructive conversations.”

The Bridge at Hoover Dam, a.k.a the Mike O’Callaghan – Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge. The arch is complete, view toward Nevada. 9 September 2009. IMAGE @Jamey Stillings

Stillings is making art with a social and political intention, that could unlock closed minds to the possibility of a civilization running on clean energy – at almost the last moment to make this most necessary transition.

IMAGES:

Jamey Stillings:

Crescent Dunes, Nevada

Ivanpah, California

The Bridge at Hoover Dam, Nevada