A study commissioned by the Chilean government and presented before the SolarPACES Conference in Morocco makes data available to potential participants in a Chilean CSP industry.

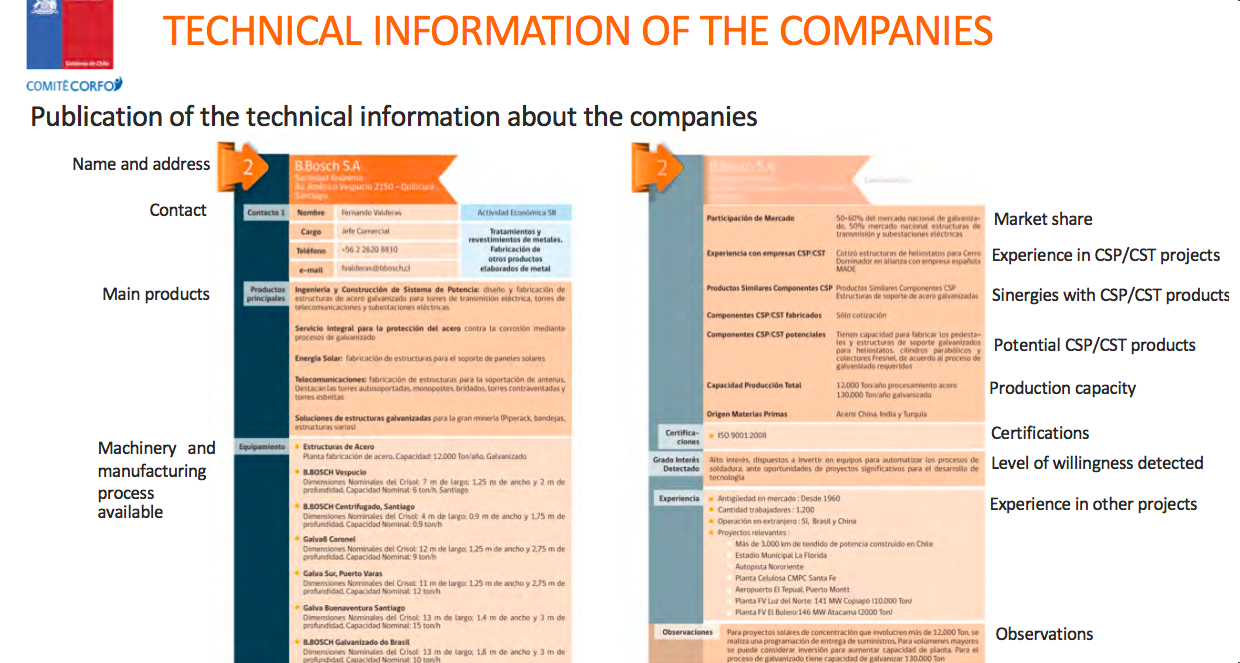

The study, Local Content in CSP:CST Projects- Assessment of the Chilean Industry is designed to put together useful information for both international CSP developers bidding in auctions and local industry groups about the potential to supply the various components.

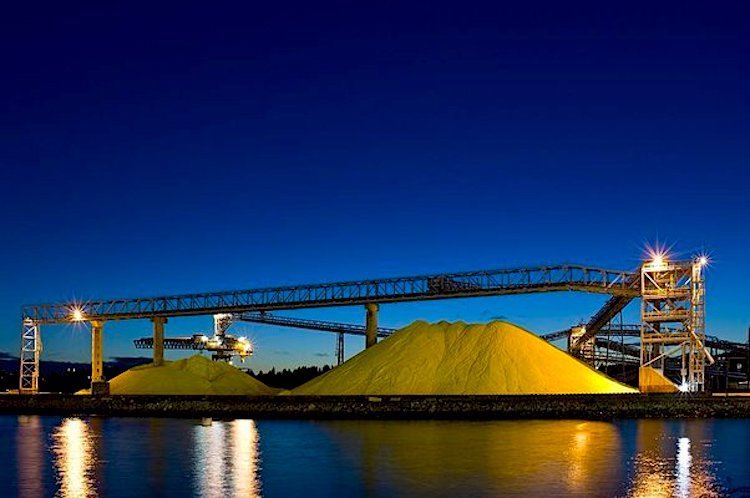

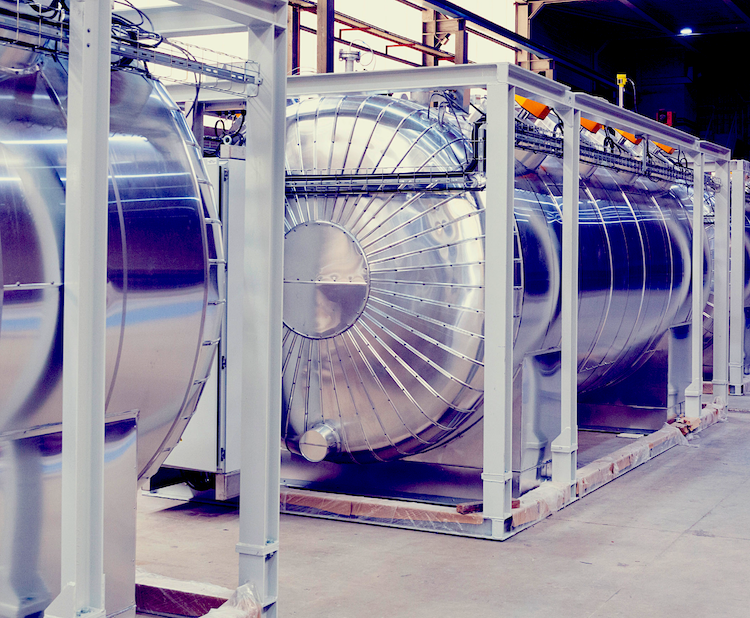

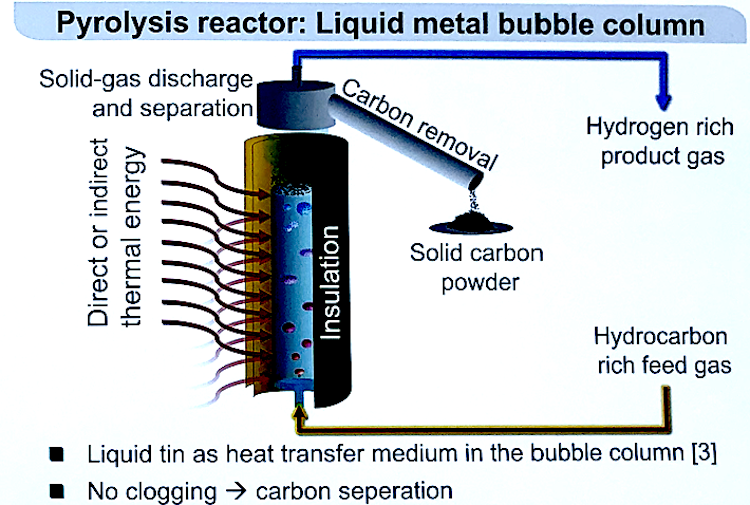

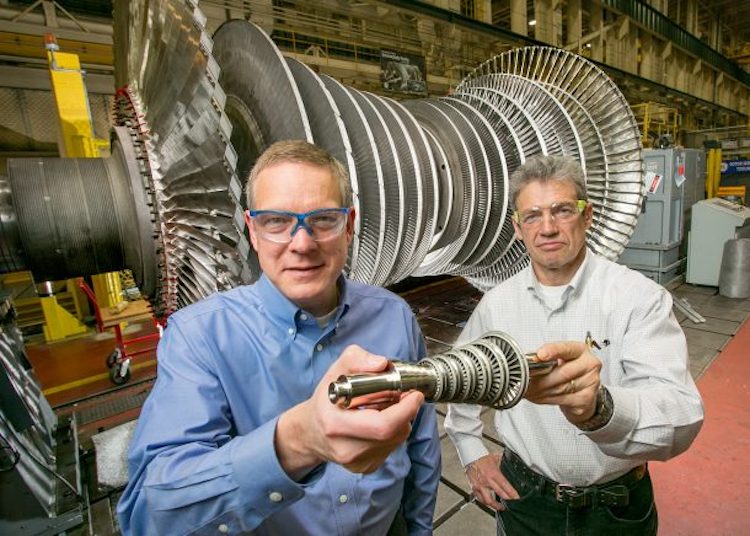

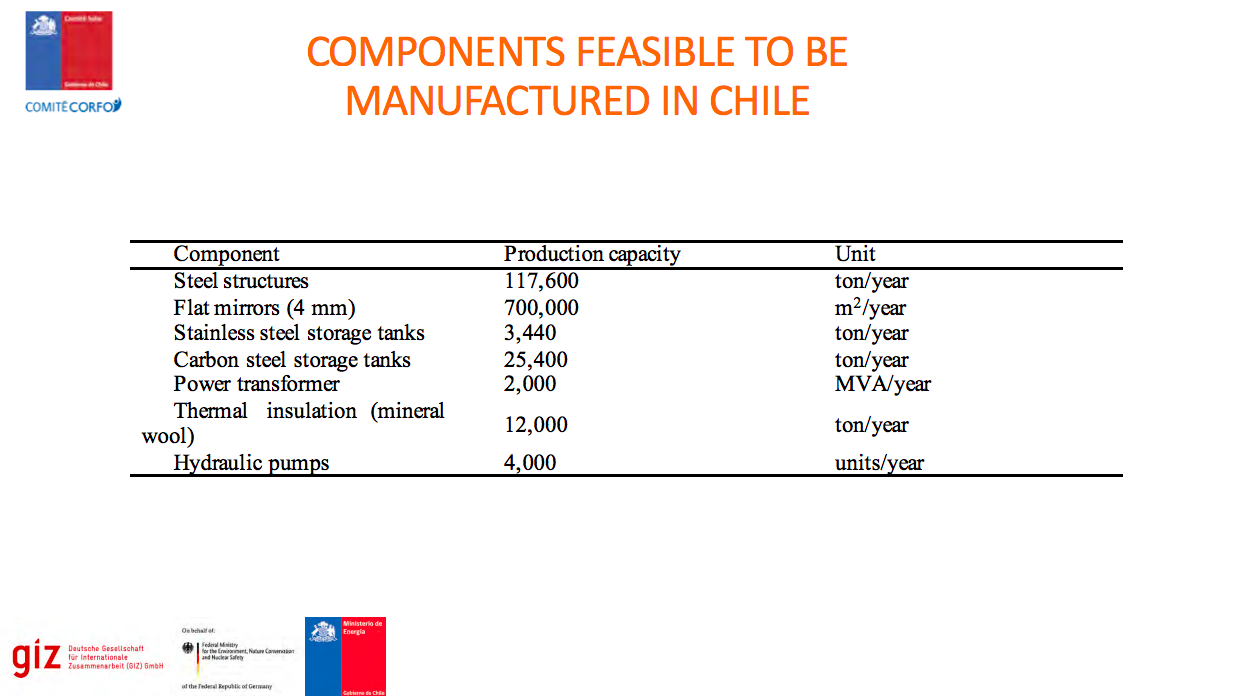

Chile is the world’s largest producer of sodium and potassium nitrates, the molten salts used in tower CSP, as well as copper and iron. The study estimates that Chilean industries could supply between 18% and 56% of the parts needed for CSP overall, and could supply most of the thermal energy storage, between building the tanks and supplying the molten salts.

To get a ‘real life’ look at both the potential, and the barriers, the study authors interviewed key industry leaders who have supplied – or turned down the opportunity to supply CSP projects.

“We think these kinds of companies in Chile can manufacture CSP components; because they produce these similar components for other industries; for the chemical and mining industry,” explained Rodrigo Vasquez Energy Program Senior Advisor for GIZ, the German agency for International Cooperation, who is one of the study’s co-authors.

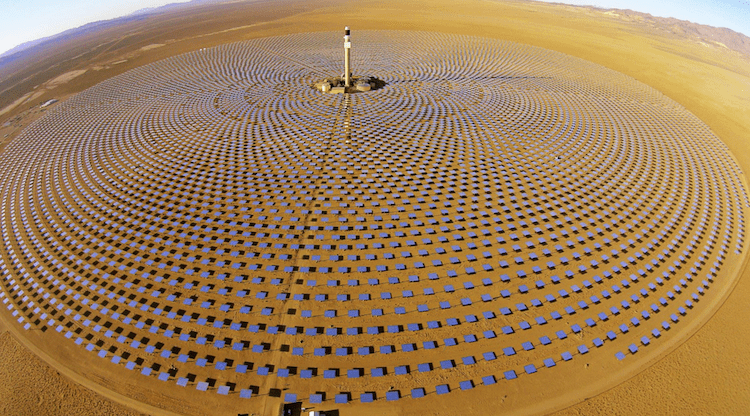

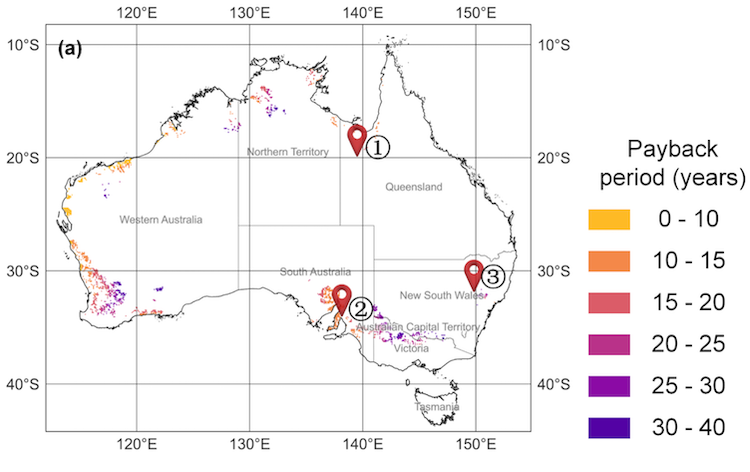

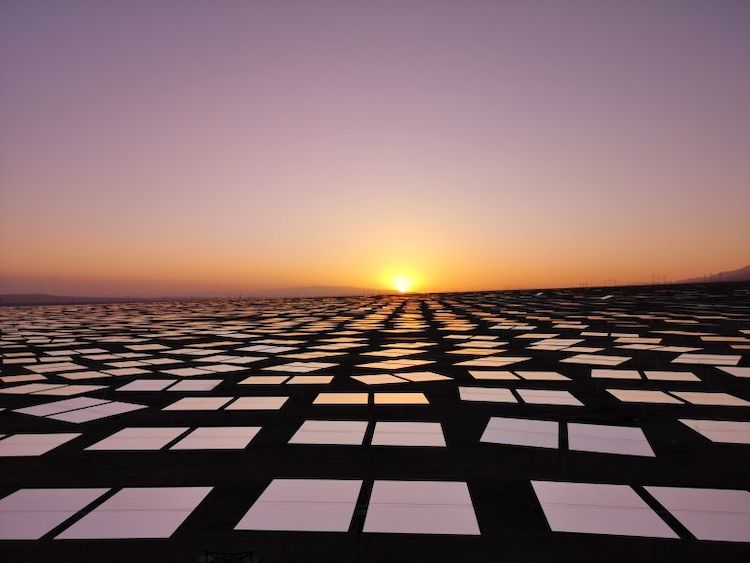

Chile has great CSP potential. Chile’s DNI is 3,800 kWh/m2 in the Atacama desert, the highest in the world, and the region is not subject to sandstorms. The grid is increasingly supplied by variable renewables, PV and wind, and to complement these renewables, flexible dispatchable generation, such as is supplied by CSP with thermal energy storage, is needed.

Meeting Chile’s 2030 and 2050 climate goals

In 2019, Chile will host COP25, and like many regions, projects ambitious renewable goals. “All the projections in Chile to 2030 and 2050 is to convert the grid to green. And all the projections say the CSP sector has the opportunity to replace this base load energy,” said Vasquez.“And that means you have to shut the gas and coal plants.”

Chile has subsidy-free open auctions which means that all generation competes to supply the lowest priced generation. Solar PV and wind have made great inroads into the fossil energy supply, based on lower prices than gas or coal. To encourage renewables, Chile had revamped its auction system, offering longer contracts to 20 years, and allowing five years from award to commissioning.

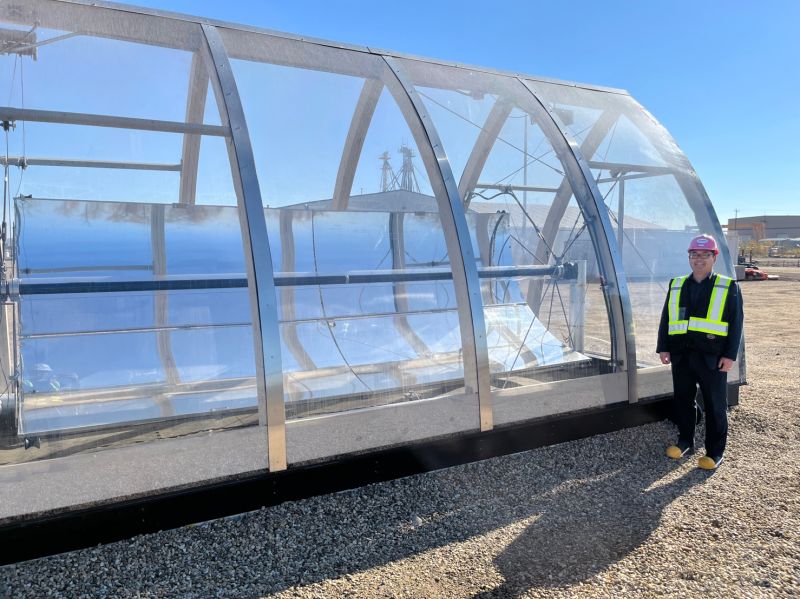

However, only one CSP bid has been awarded in a Chile auction. This project, Abengoa’s Atacama-1, awarded in 2014, and now renamed Cerro Dominador, is the only CSP project under construction there. But as a result of the firm’s unrelated financial problems, halfway into completion, it laid fallow for two years. This soured local views.

“When the Cerro-Dominador project stopped it was not a good thing,” said Vasquez. “The companies looked at that not so well.”

Cerro Dominador was refinanced under new ownership (EIG Global Energy Partners) and resumed construction in mid 2018 and is now expected to be commissioned in 2020. Vasquez projects that its performance will be the ‘make or break’ for the future of CSP in Chile.

“Because if this project fails maybe the CSP in Chile will have a hard future,” he said. “But if this plant works fine I am very sure that not only will Abengoa (EIG) build other plants, but there will be many others.”

Lack of predictable pipeline of CSP is an obstacle

To grow, labor-intensive heavy industries like CSP need the certainty of an ongoing pipeline, which is typically implemented by auctioning a known capacity specifically for CSP as in China, or by auctions in a predictable series of rounds as in South Africa.

For example, the UK offered rounds of auctions with known capacities announced in advance for offshore wind, a similarly heavy marine industry. Only the certainty of a continuing pipeline makes investment practical for suppliers.

The study authors encountered this reluctance when talking to industry: “They say: ”I need to have a big projection over time because to make this new element. It will need new production lines and that is a very high investment for me.”

Vasquez concluded that without the security of an ongoing pipeline it will be very difficult to develop in a CSP market in Chile. With only the one project, Cerro Dominador, awarded to date, domestic suppliers are reluctant to modify assembly lines with no guarantee of future commissions.

“Manufacturers don’t have the capacity to produce a big amount of components in a short time. They think why would I extend my production line to produce this one CSP element for just one project,” he explained.

CSP is much more dependent on local engineering skills and manufacturers to supply parts than PV, which can be easily imported. But Chile makes no requirements that a certain percentage of a project be supplied locally.

“Chile should consider other factors like more jobs, more industries,” said Vasquez, who thinks it would be desirable to adopt such models. “Chile has a very open market, with no subsidies. That makes it harder for nascent technologies such as CSP, so the government is now looking for other ways that it could incentivize such newer technologies that have great local industry development potential.”