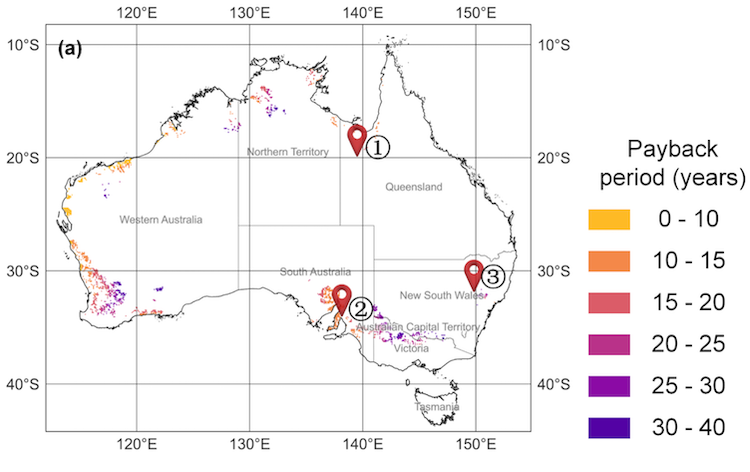

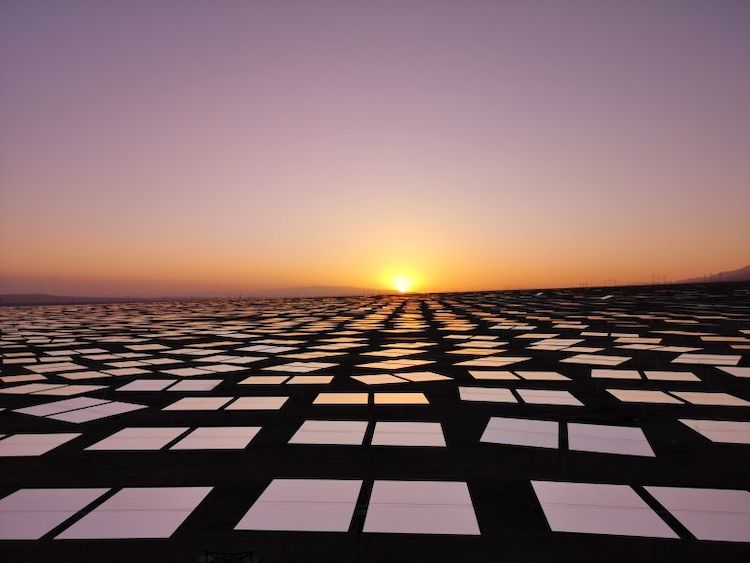

IMAGE @ Johan Lilliestam: How CSP expertise moves from nation to nation as development is incentivized

As China closes in on doubling today’s entire total global capacity of Concentrated Solar Power (CSP), a new paper, The Dragon Awakens: Will China Save or Conquer Concentrating Solar Power? analyses the potential impact that the nation’s ambitions, and record-low costs, might have on global CSP – both good and bad.

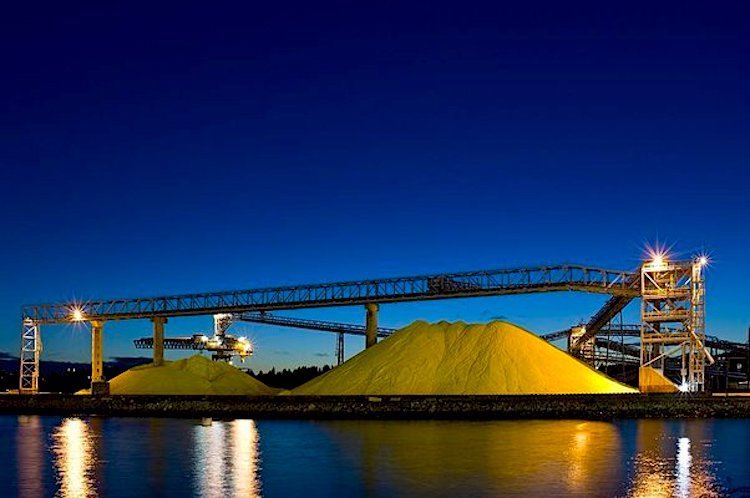

“The cost of Chinese CSP stations under construction is 40% lower than that of plants built elsewhere. We conclude that the Chinese support programme has thus succeeded in its central aims of leapfrogging and has built up a domestic industry capable of building stations and most components at lower costs than foreign competitors,” the paper states, noting that China’s Levelized Cost Of Energy(LCOE) even in its first year, 2018, is under 10 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh).

“China’s low prices are a positive development for CSP,” said lead author Johan Lilliestam, who presented his paper at the 2018 SolarPACES Conference held in Morocco.

He makes the point that with China in the game, the outlook for the technology has gone from from gloomy to better than ever – however that it also carries great risk.

“There is a scenario in which overoptimistic bids destroy international confidence in CSP as a whole,” Lilliestam cautioned. When novice entrants in a market offer unsustainably lower prices, there is the possibility that if they fail it could bring down the market.

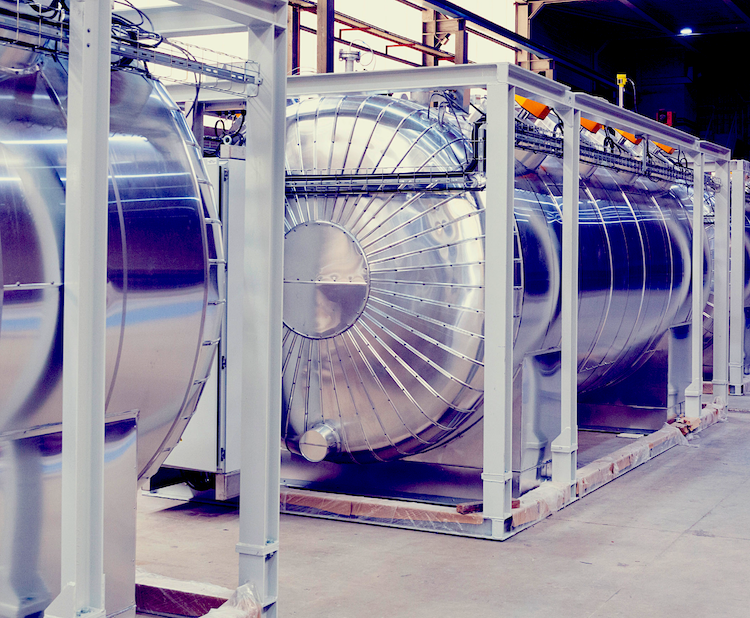

Supcon 50 MW tower CSP connected to the grid in January 2019 IMAGE@ CSPPLAZA

A fierce competitor in renewables

A similar low bid strategy led to China’s current world leadership in wind and photovoltaic solar.

The paper notes that, while in 2005, Chinese companies held only 1% of the global wind manufacturing capacity, today almost 50% is Chinese, and that its domestic wind market is installed at 40% lower costs compared to its European and American counterparts.

Just three years after China began PV manufacturing it owned 30% of the world market. By 2015, it outcompeted most incumbents in Japan and Europe with 70% of the market, and now leads the world in domestic installation as well. China now has a history of overachieving its five-year renewable energy targets.

Now China’s focus has turned to CSP

In China’s current five-year plan CSP is singled out as one of 12 “mega-projects of science research” and as one of the “key energy technologies.”

Currently, the first stage of its 5.3 gigawatts (GW) plan is under way, designed to shake out the most able among a very large number of Chinese competitors.

Initially, to develop practical experience, 1.3 GW comprising multiple initial projects are being built at full size, 50 MW and 100 MW. Following this demonstration programme currently underway, the plan is to build another 4 GW of CSP in addition, by 2022.

IMAGE @IRENA China’s share of renewable patents. In China’s current five-year plan CSP is one of the “key energy technologies” singled out as one of 12 “mega-projects of science research.”

Of the two nations with the most CSP to date, Spain built 2.3 GW and the US built 1.3 GW.

The paper notes: “If successful, China would in only five years have added as much CSP capacity as all other countries combined since 1984 [14], making the expansion outlook better than in a long time.”

“One of the explicit goals of the research strategy is to build up a new industry in China, and leapfrog the European and American industries,” Lilliestam noted.

A return to the early days of feed in tariffs

The approach China is taking to achieve its ambitious CSP goal reverses a trend in renewable policy. Globally, the trajectory for solar bids has trended towards open competitive auctions.

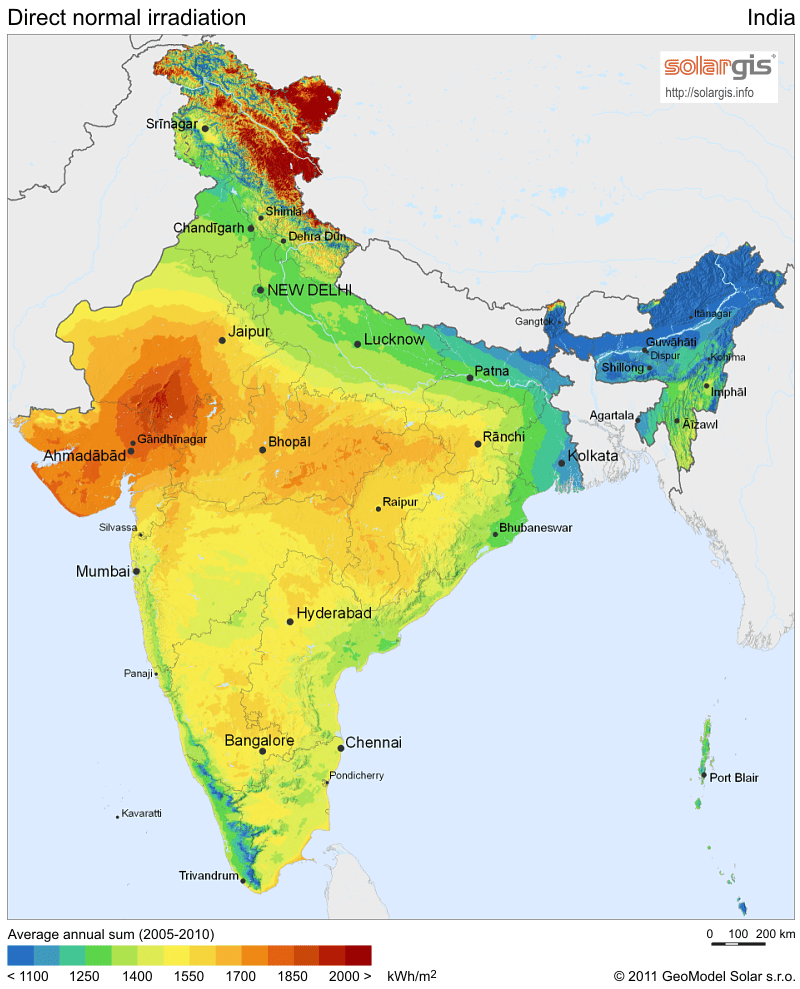

As a dispatchable form of solar, in Chile for example, open auctions require that CSP competes against entrenched fossil energy industries for dispatchable generation, as with thermal energy storage CSP can generate power at any time. In most nations, competitive auctions have pitted all the renewables against each other for a slice of a renewable quota.

China however, chose to return to an earlier policy driver, that was used to grow the first major CSP industry; Spain’s feed-in tariffs, where the government guarantees a fairly generous set price for every delivered kilowatt hour of generation in the new technology.

Lilliestam points out the thinking behind the feed in tariff. “It depends on what you want,” he explained.

“Do you want to emphasize the static efficiency of low costs now or do you want to maximize the dynamic efficiency of lowering costs over time. It would certainly appear that China has taken the long-term view.”

Nurturing a young technology to growth

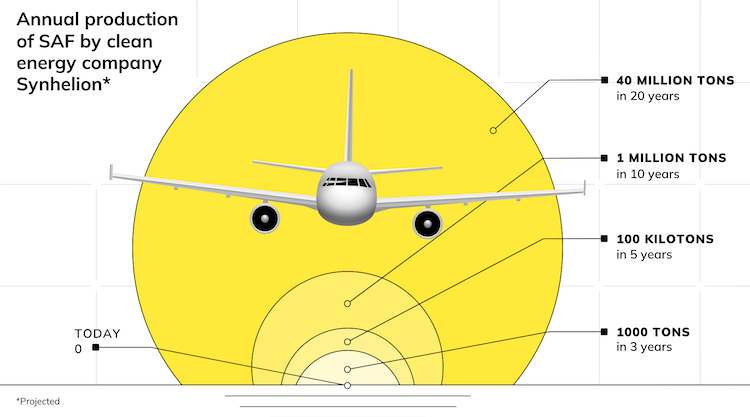

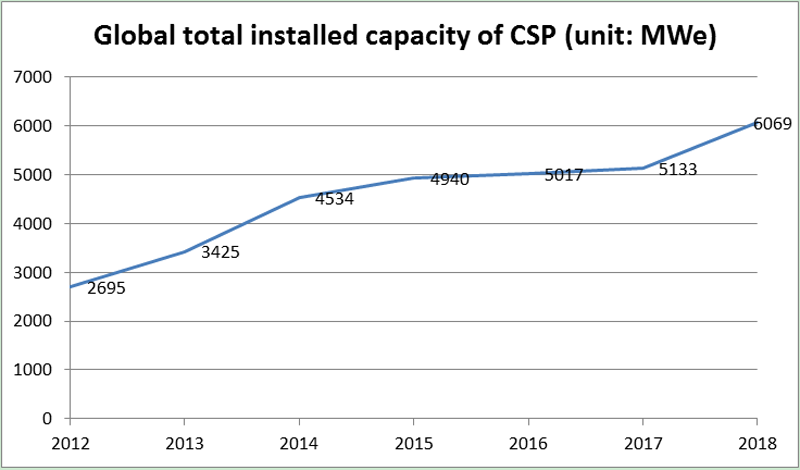

Compared to the hundreds of gigawatts of PV installed globally, CSP is in its infancy, with just 6 GW installed, of which tower (How CSP works, trough, tower, Fresnel and Dish) comprises less than 500 megawatts.

China has taken the approach of “developing industrial commercial-scale projects on the ground (or learning by doing) to allow the new industry to develop, learn and improve processes and procedures,” the paper notes.

“I think a feed in tariff is the better strategy because CSP is an immature technology,” Lilliestam commented.

“The advantage is that gives you a lot longer and steadier pipeline of projects and it has lower risks to the companies involved,” he explained, pointing out that in any immature industry, new firms that spring up tend not to be very strong financially.

“If what you want is to build up a new industry, to develop this immature technology, protect it from market forces and build it up to make it competitive over time, then a feed in tariff is well suited.”

By contrast, competitive auctions don’t nurture long term development in nascent technologies, he said. “The rationale behind an auction scheme is that you could get lower costs,” he said.

“But then usually you construct just one project, so you don’t get a clear project pipeline, and supply chains are not expanded. When the cost pressure is high you don’t really get the technology and industry development that you get under a feed in tariff scheme.”

IMAGE @ CSPPLAZA Low construction rates 2015-17 hit the CSP industry hard, and many suppliers were struggling financially or left the market altogether

After the global deployment hiatus, LCOE increased

The normal trend in new renewables is for LCOE to go down as deployment goes up. But between 2015 and 2017, the CSP pipeline was abruptly ended, and LCOE actually rose.

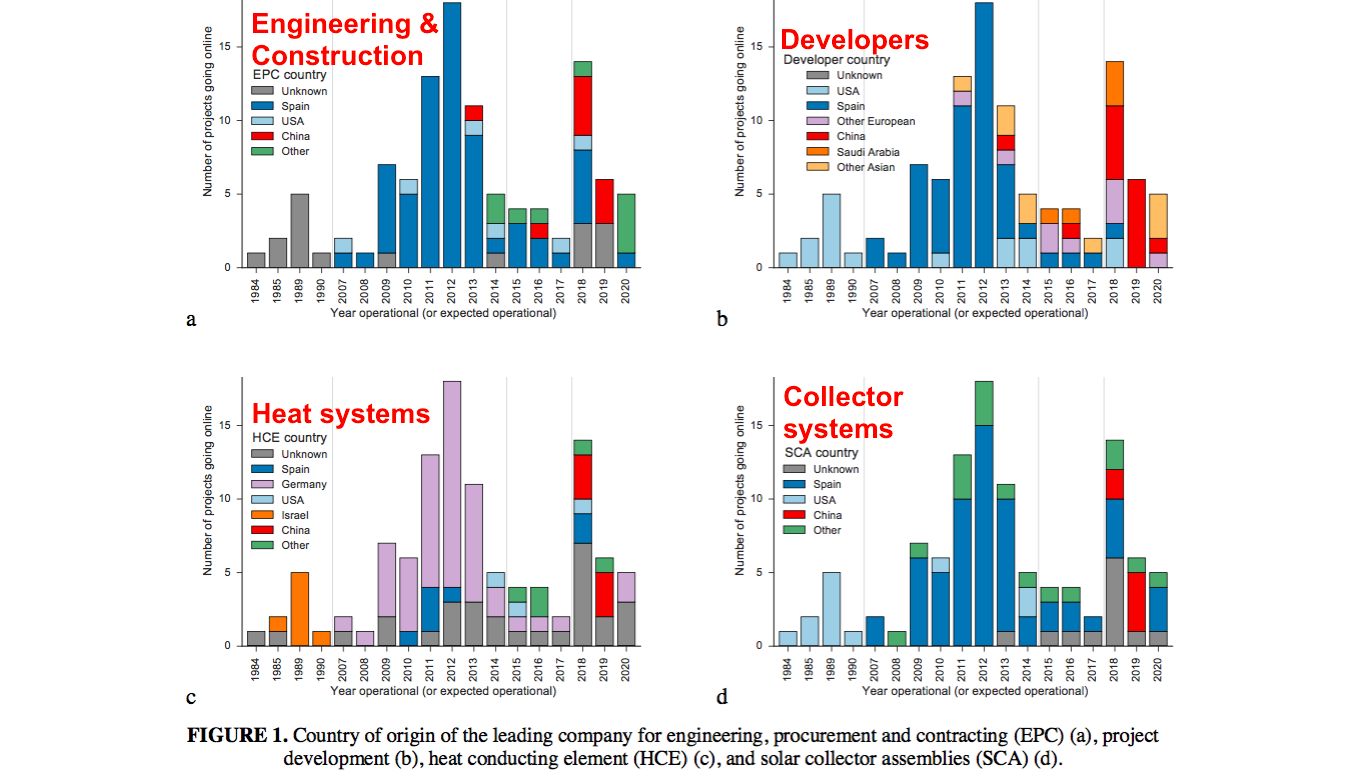

First in Spain and then in the US, change in political support halted further deployment of CSP. So once the last project finished construction in 2015, demand evaporated. The CSP supply chain for heliostats, receivers and heat transfer fluids thinned out as a result.

Spanish and US firms then moved to new markets overseas, but supported by a mere handful of remaining suppliers.

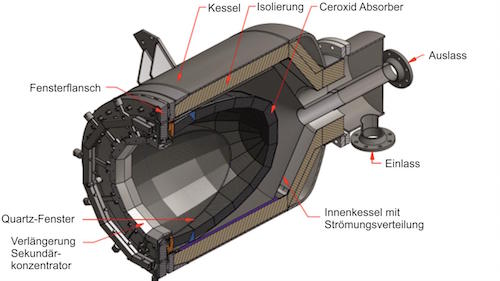

Expertise transfer also becomes lost, Lilliestam said: “In CSP it is much harder for knowledge to spread to new countries and projects. Transfering knowledge is much harder for an engineering technology like CSP than for a mass-produced technology such as PV.”

LCOE went as high as 22 Cents/kWh due to this industry lull from 2015 to 2017. (IRENA Power Generation Costs in 2017) Then, new projects began construction in South Africa, Morocco, Dubai, Chile and Israel and resumed the LCOE trajectory, dropping to 17 cents/kWh; but higher than if there’d not been the hiatus.

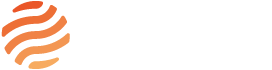

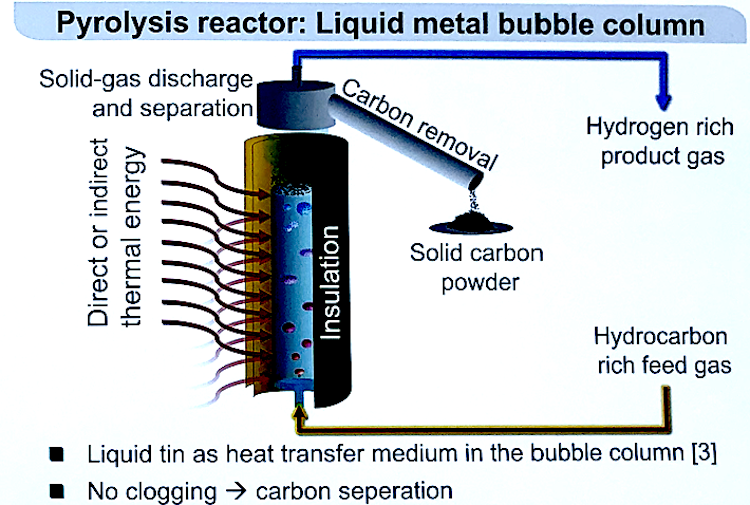

China’s 1.3 GW of “learner CSP” helped reduce global LCOE

By contrast, there was a “Cambrian explosion” of Chinese firms responding to the pilot program, so that more than half of the 1.6 GW of CSP under construction globally in 2018 was Chinese, driving global LCOE to under 10 cents per kWh.

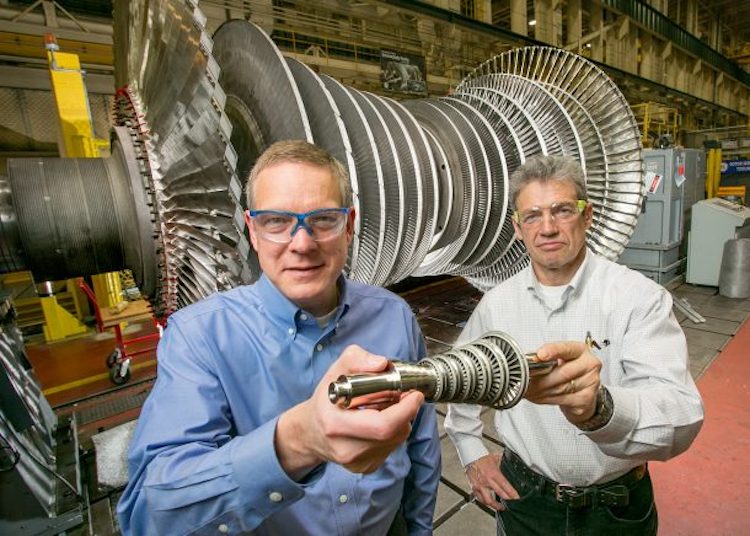

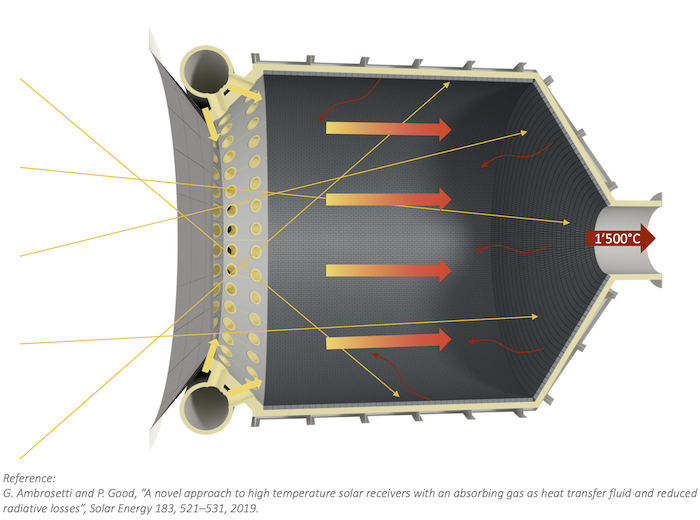

China’s low cost is surprising, considering two facts. One, that China was completely new to all but the power block components of building CSP (as a thermal technology, its power block involves the same machinery as other thermal power that China has expertise in, like coal).

And secondly, that about half of China’s new projects utilize the newest CSP technology; tower with storage, that has not yet racked up the level of deployment needed to reduce its costs compared with trough, the earlier CSP technology.

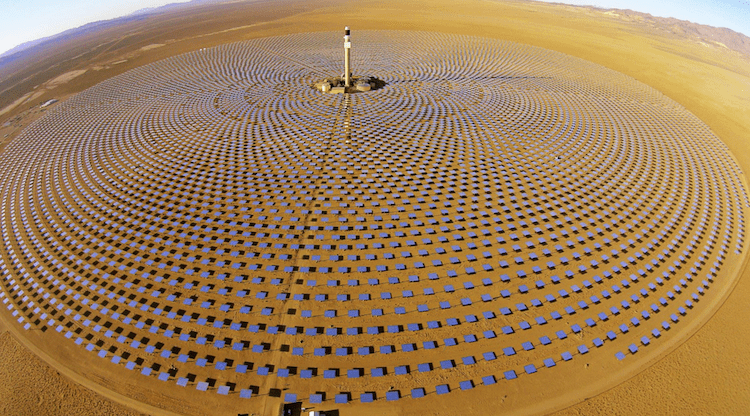

In CSP, current projects typically include up to 15 hours daily of thermal energy storage IMAGE @Lazard

But China’s low bids bring high risks

Although western firms were able to compete in the pilot, none won any bids except Abengoa, for 50 MW of trough. Even as startups, Chinese firms were the most aggressive bidders.

“It may be economically sound to underbid for a project in China just to get it up and going, to show that the company can do it, which may be a prerequisite for new companies to get further projects, in China as well as outside of China,” explained Lilliestam.

The first of the Chinese firms to build outside China is Shanghai Electric, in a consortium with ACWA Power on Dubai’s DEWA project comprising 600 MW of trough with ten hours of storage plus 100 MW of tower CSP with 15 hours of storage. DEWA broke price records, bid at just 7.3 cents per kWh.

“But something is nonstandard in that bid,” Lilliestam cautioned. “In any case, it seems that none of the involved companies will be making a lot of money on that particular station.” Tower is a newer technology so it still costs more than trough, and within the DEWA project the tower portion includes more hours of storage (15 hours) than the trough (10 hours).

DLR Director of Solar thermal Research, and SolarPACES Chair Robert Pitz-Paal also emphasized how much rides on what could be precocious overseas ventures by unseasoned Chinese firms. “If they fail, this may become the coffin nail for the technology as the confidence of clients in CSP and its potential for cost reduction may be damaged strongly by Chinese suppliers,” he said.