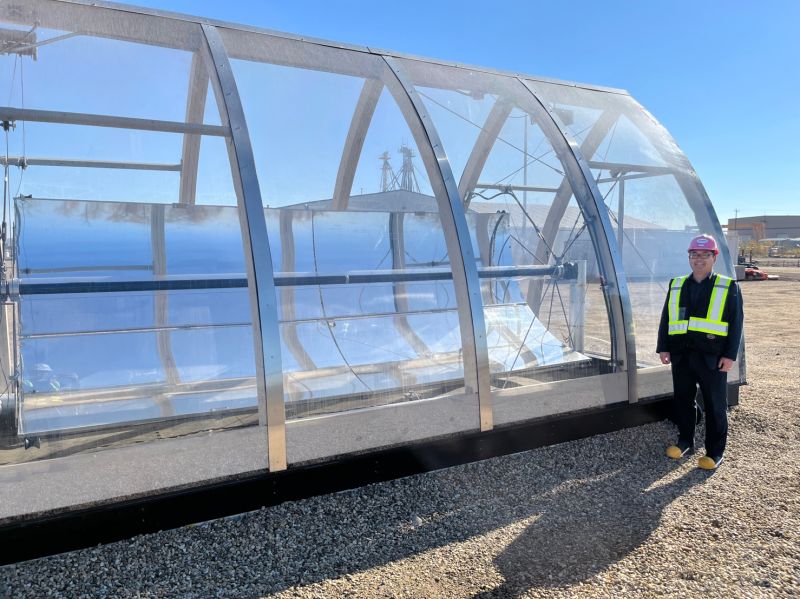

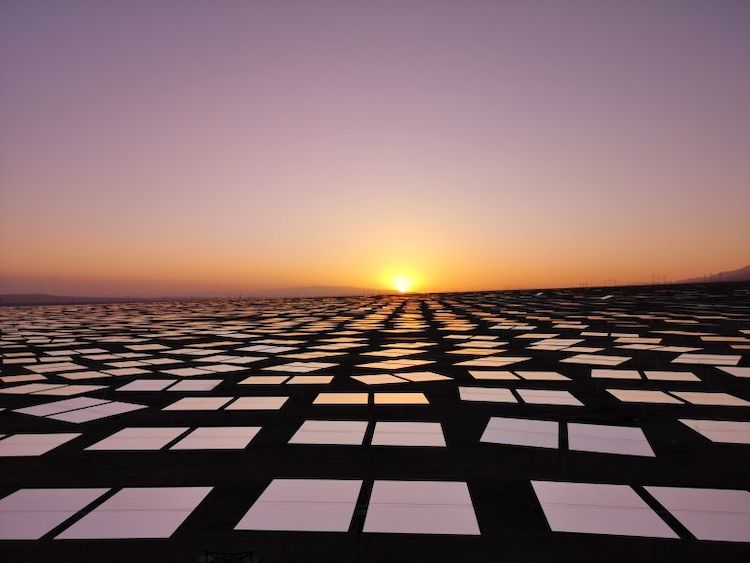

IMAGE CREDIT: Wikipedia – Atacama, Chile

The moment the market received a signal that a large number of gigawatts would be tendered, “costs came crashing down. That is what CSP arguably needs, and I think we’re not that far from that point.”

CSP Today reports:

The tender process favored by the likes of Chile and Dubai has done more than anything else to drive CSP prices to record lows, according to Ranjan Moulik, head of renewables at investment bank Natixis CIB.

Moulik has specialized in renewables since 2003. Speaking at CSP Seville, he cited Brazil as one of the pioneers of renewables tenders, saying wind power reached price parity with electricity generated from fossil fuels by the time of the country’s second tender auction in 2009.

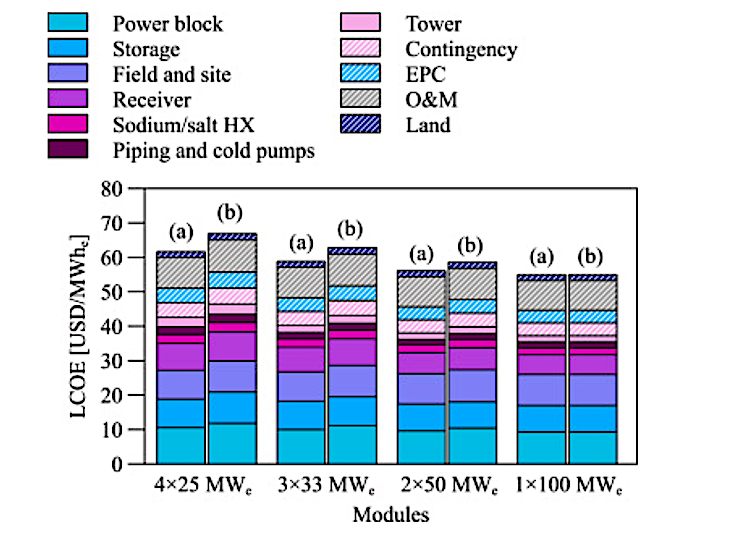

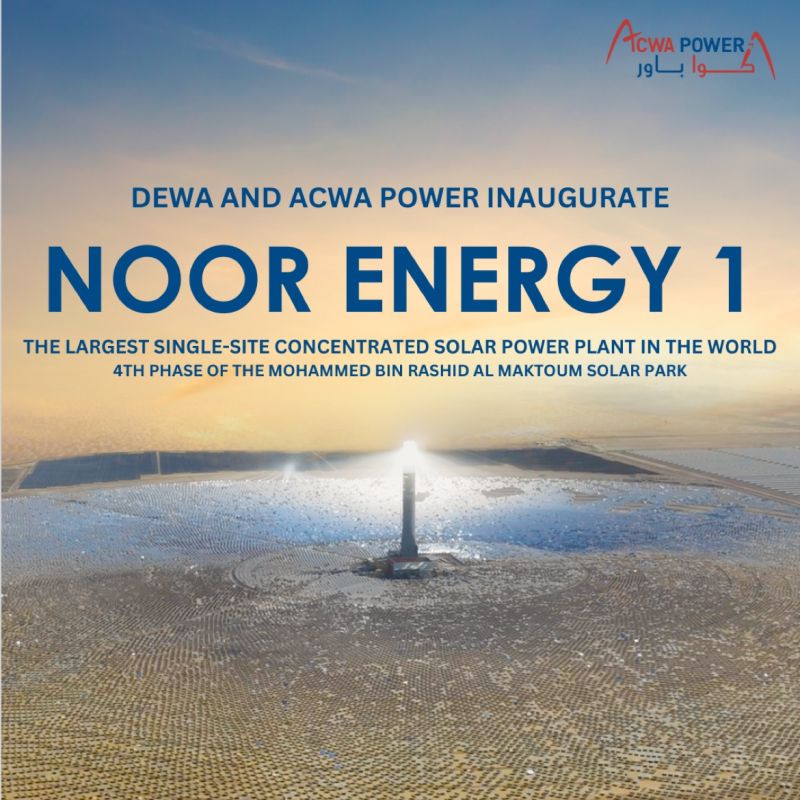

Natixis is one of two international banks involved in financing DEWA, the 700 MW project in Dubai for which developer ACWA Power has submitted a $73/MWh tariff. In October, SolarReserve said it bid less than $50/MWh for 24-hour solar in a Chilean auction – the lowest bid on record for a CSP project. The winners of Chile’s latest renewables auction, representing a range of technologies including wind and CV, submitted an average of $32.5/MWh.

“It is the tender system that has really managed to drive prices down, because it forces you to be competitive. It in turn forces you to make your suppliers competitive, and if the market signal that is sent out by the regulator is current, meaning the regulator can tell you in the next few years the amount of gigawatts it expects to come online, then the supply chain will adapt themselves, they will invest to make sure costs get driven down,” Moulik said.

This has been seen in various industries, including offshore wind, where the moment the market received a signal that a large number of gigawatts would be tendered, “costs came crashing down”, he added.

“That is what CSP arguably needs, and I think we’re not that far from that point.”

Three phases of learning

Reflecting on the things he has learned from his time in the business, Moulik argued there have been three distinct phases in the life of concentrated solar power.

The first phase involved the initial experiments in California’s Mojave desert, where he noted some projects had recontracted after 25 years of operation and were heading for a total project life of 40-50 years. Spain dominated the second phase, and as time has gone by the eight projects financed by Natixis there “have stabilized and are (now) performing better than expected.”

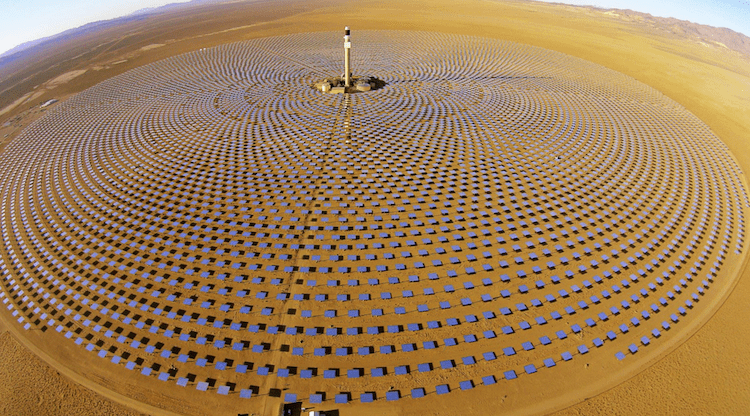

Technology-agnostic tenders create competition for CSP developers

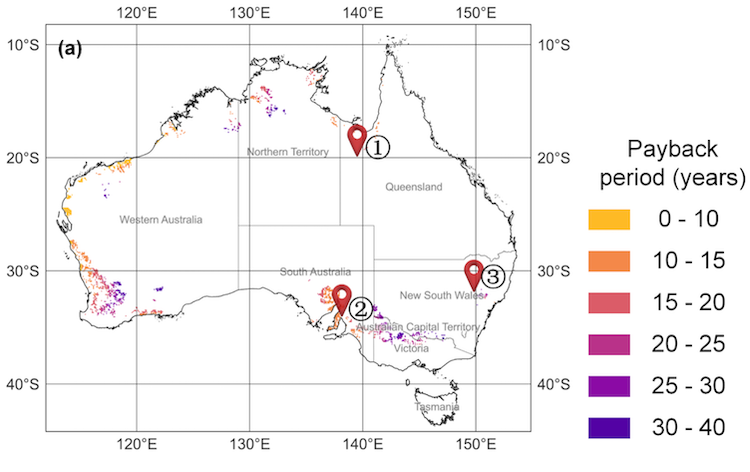

Chile recently awarded 2.2 GW in renewables tenders at an average LCOE of $32.5/MWh (Image: Chilean National Energy Commission)

The third phase is centered around the Middle East. Of Dubai, he said “we’ve come to the point where we are optimistic as a financing community that this is a technology that is here to stay. It’s not going to solve everything in every place, (but) it has found its niche.”

The United Arab Emirates has posed some challenges, he noted. Natixis financed Shams 1 in Abu Dhabi, developed by Abengoa and Total. Although the regulatory environment was stable, the natural environment is less so. Shams was the first CSP plant to be constructed in a Middle Eastern desert environment, Moulik recalled, and one of the first things the project developers discovered was what sand can do to parabolic troughs.

During the day the sand would fly in and settle into a concave cavity, and then at night when the temperature cooled, there would be condensation, and the sand would stick. The developers solved this problem by building a wall around the entire project, and eventually the plant stabilized and performed even better than expected. He said that one thing the investors learned from the project was that despite the many challenges, the key is to keep on board those people who know the project well.

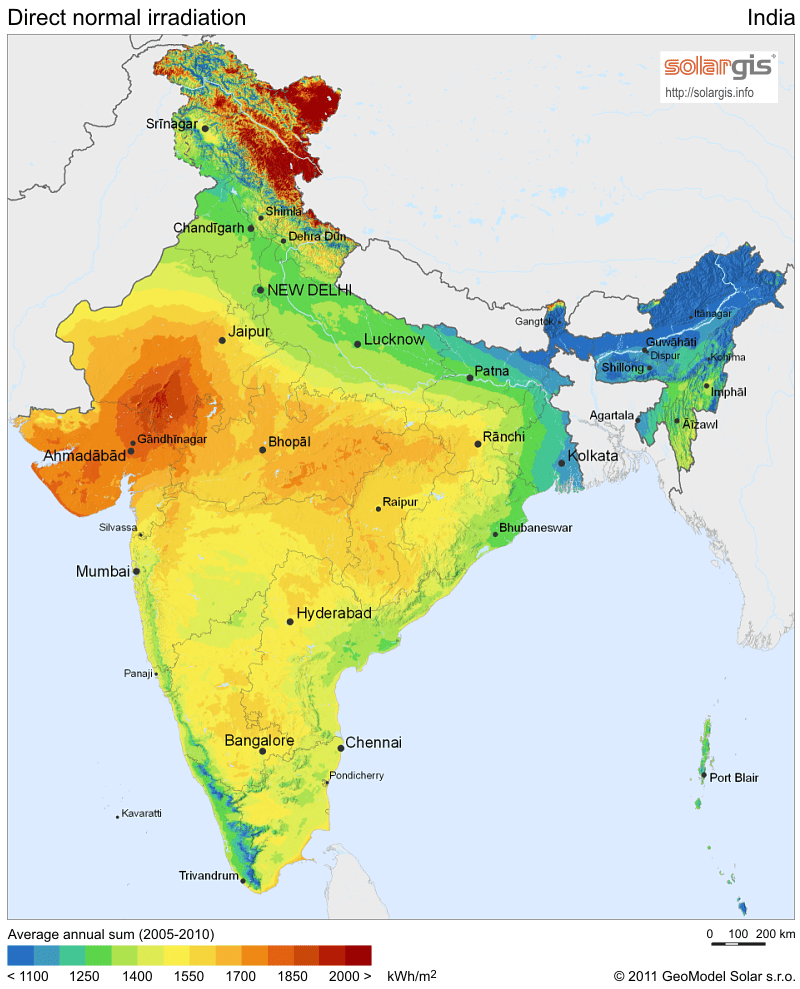

Finding the right location

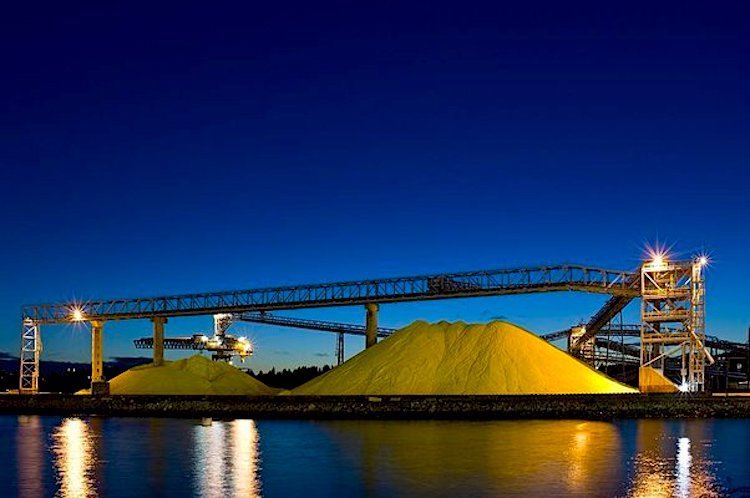

Aside from a stable environment and high Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI), the other important factor in selecting a location for a CSP project is land, Moulik said. “By its very nature, CSP needs scale in order to be cost-effective. And when you’re looking for scale, you need huge amounts of land, and in general one tends to find huge amounts of land in very secluded areas which are not necessarily connected to the grid.”

In Chile, Natixis is one of the investors behind Abengoa’s 110 MW Atacama-1 PV-CSP project in the Atacama desert in the country’s north. Despite the many delays caused by Abengoa’s financial restructuring, Moulik said the project would “hopefully be financed early next year”. On the other hand, he said Chilean regulators expect developers to take big risks, a problem exacerbated by the connectivity issues between the northern and southern grids, which he noted has led to lots of stranded projects in the Atacama region.

South Africa is another country with abundant land where the regulatory environment has proved a challenge. Moulik said the 100 MW Redstone CSP project can benefit from good DNI, good sponsors and proven technology. But when a project has an offtaker in financial difficulty – in this case the national electricity utility, Eskom – they will try all manner of ways to duck out of their obligations, he said.

“This is what has happened here, because this project is secluded, not connected to the grid, the utility needed to make an investment, and it was too much for them financially – the project has been in limbo for four years.”

According to Moulik, Eskom calls ACWA Power twice a year to say they are ready to sign, but they never deliver on this.

Source: http://analysis.newenergyupdate.com/csp-today/competition-pv-and-wind-sees-csp-bids-fall-low-50mwh