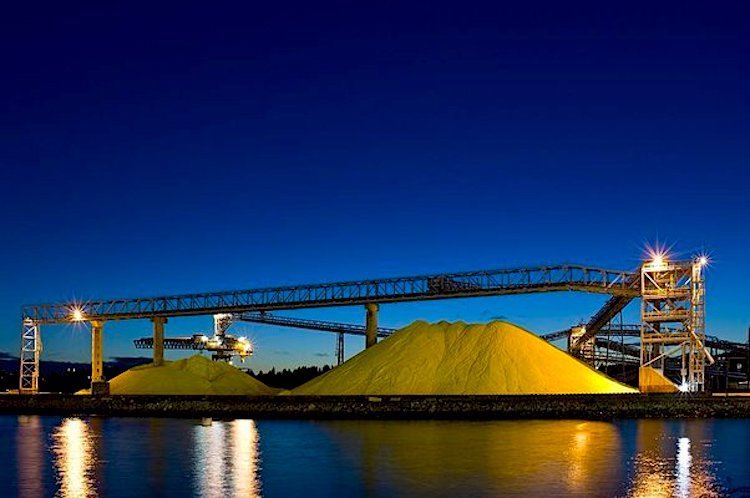

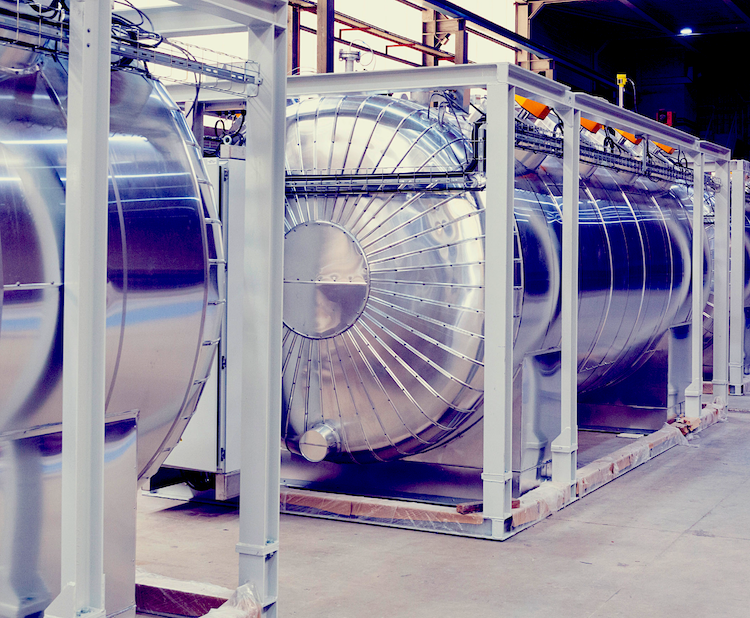

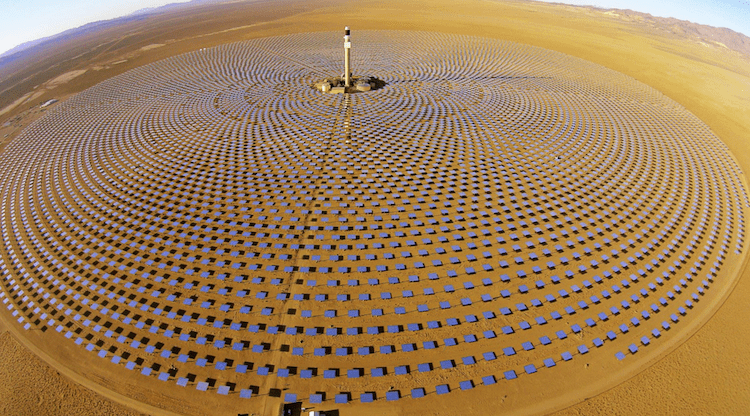

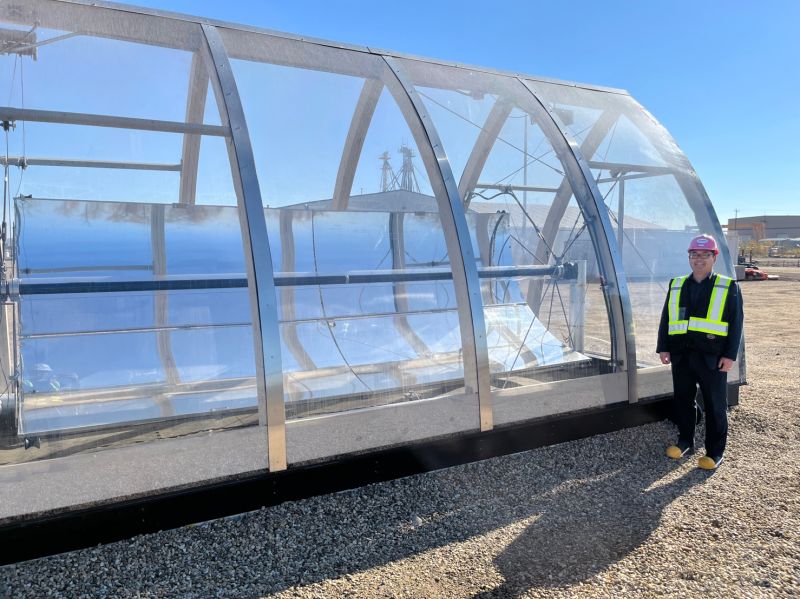

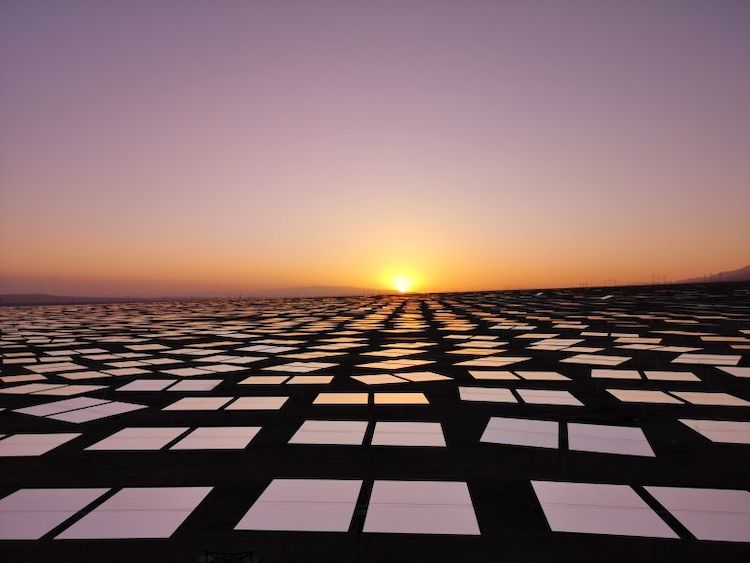

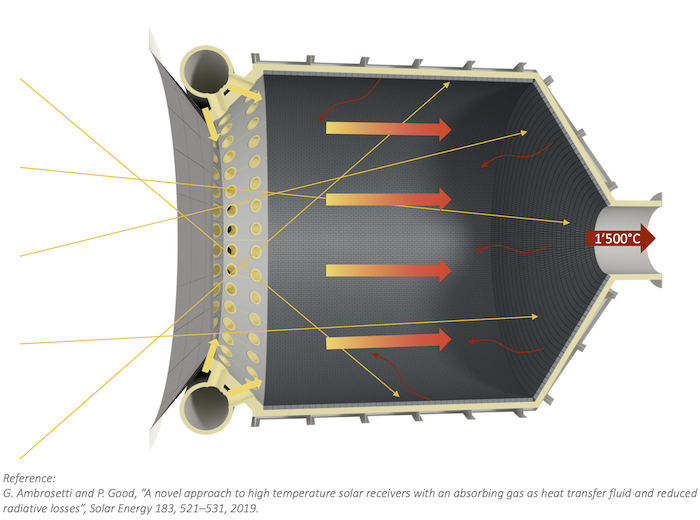

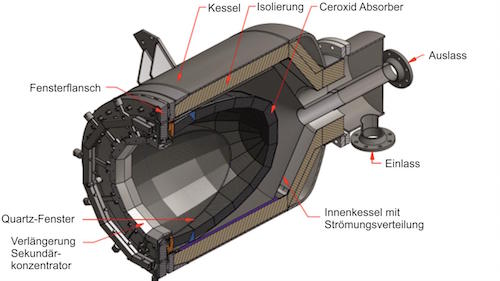

With its cheap thermal energy storage making it dispatchable, Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) could replace its dispatchable counterpart in fossil fuels – natural gas, Lilliestam argues. IMAGE@Kevin Sara

For the last decade, the EU has prioritized coal phase-out to meet its climate goals, given coal’s greater carbon emissions, while natural gas has kept a temporary job as a “bridge” necessary to firm intermittent renewables with its dispatchable generation.

“We were supposed to expand wind and PV and balance them with gas power for the next 10 or 15 years. And now, all of a sudden we cannot do that anymore. So we need another balancing technology to fill this flexibility gap,” professor Johan Lilliestam from the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies in Potsdam revealed in a call from Germany.

But the Russian invasion of Ukraine has upended this relationship for the EU, putting the gas problem on the front burner, and that gives CSP, the dispatchable form of solar, a leg up.

“In Europe, finding ways to replace gas even before we replace coal has gained quite some urgency in the last months. In the past, we thought to get rid of coal first because it is worse for the climate. But what has happened now is that we’ve lost our transition fuel,” he explained.

As Brussels puts together its REPowerEU plan for green-led energy independence from Russian gas, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said that “the EU must reduce rapidly our reliance on Russian energy: We can.”

Replacing gas first is the EU’s new focus

This new situation makes the case for CSP much stronger.

“This new policy outlook greatly affects the business case for CSP, because CSP can fulfill the same functions as natural gas does today, so we could replace gas power stations on a one to one basis with CSP plants. I would argue it is pretty likely that a new CSP station would be cheaper than a gas power station at these gas prices,” Lilliestam commented.

Lilliestam, who leads the Energy Transitions and Public Policy group at IASS is lead author of the new paper, Deep decarbonization of the European power sector calls for dispatchable CSP that already argued that as the dispatchable renewable due to its capacity for on-demand generation, a lot of CSP is needed to meet the EU’s deep decarbonization targets.

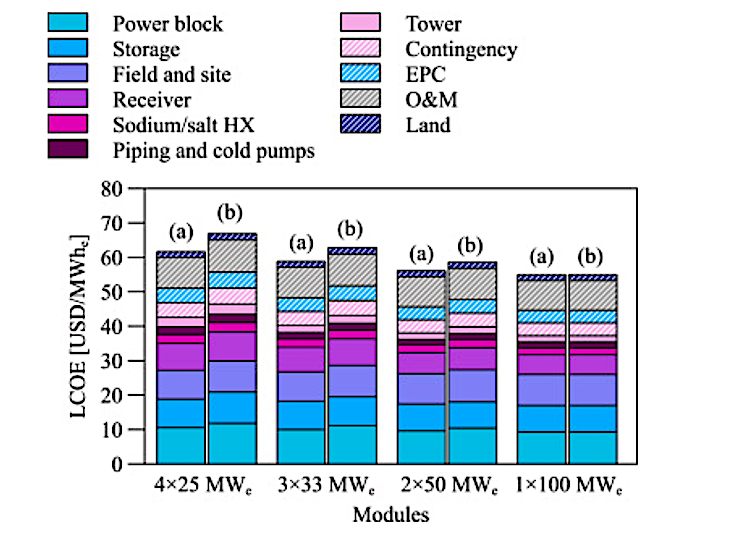

“This would require increasing the current European CSP fleet by a factor of 20 to 60 in the next 30 years. To achieve this financial support between € 0.4-2 billion per year into CSP would be needed, representing only a small share of overall support needs for power-system transformation,” the paper states.

The REPowerEU plan will increase the 2030 renewables target from 40% to 45%, with solar PV alone doubling from today’s capacity to 320GW by 2025, with a further boost to almost 600GW by 2030.

To enable faster growth; the plan envisions dedicated regions for faster project permitting as the bloc formally recognizes speeding up renewable energy deployment as an “overriding public interest.” Faster, easier permitting would greatly reduce the cost of CSP deployment in particular.

CSP is now competitive with natural gas

The original Spanish CSP was built with Feed-in Tariffs. By guaranteeing the price – at least till an abrupt shut down – these worked well to begin a supply chain of Spanish expertise in a new technology, but failed to gradually reduce payments as capacity increased, so ultimately failed to deliver low CSP prices.

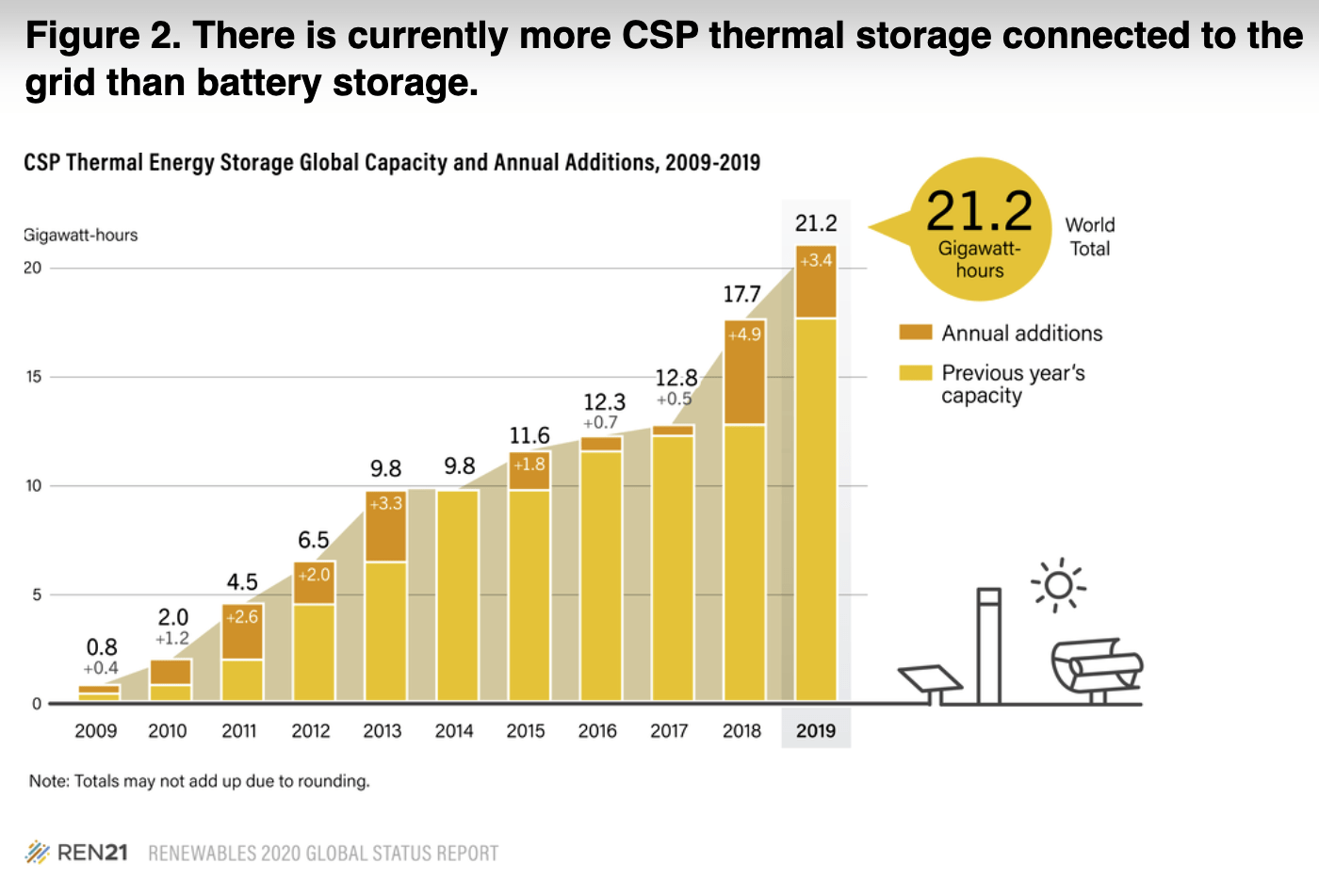

But since then, auctions have become the norm globally (with or without a “time of use” carve out, for evening renewable generation, for example) and CSP can now be built for much less, especially as China now sends its expertise abroad to new projects in Morocco and Dubai, where projects came online for as little as 7 cents/kWh. (All CSP now includes up to 12 hours of thermal energy storage daily, the key to its flexibility.) As China’s new domestic CSP ramps up, it outcompetes coal at 5 cents. Chile’s permitted Likana project saw its first 3 cents bid last year.

Eastern Europe is especially captive to this unstable supply

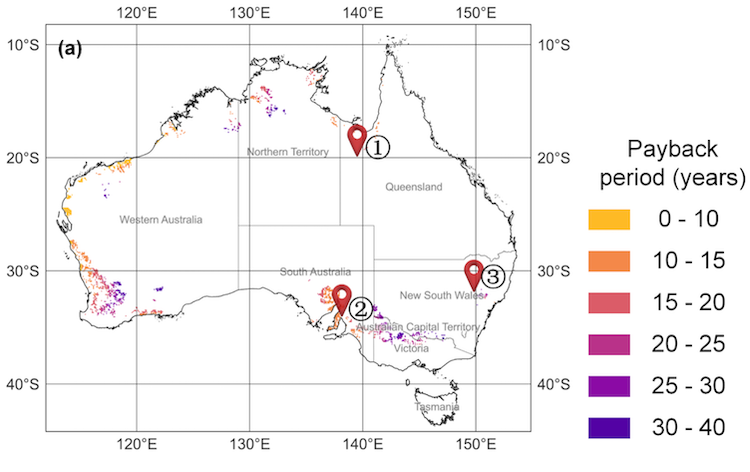

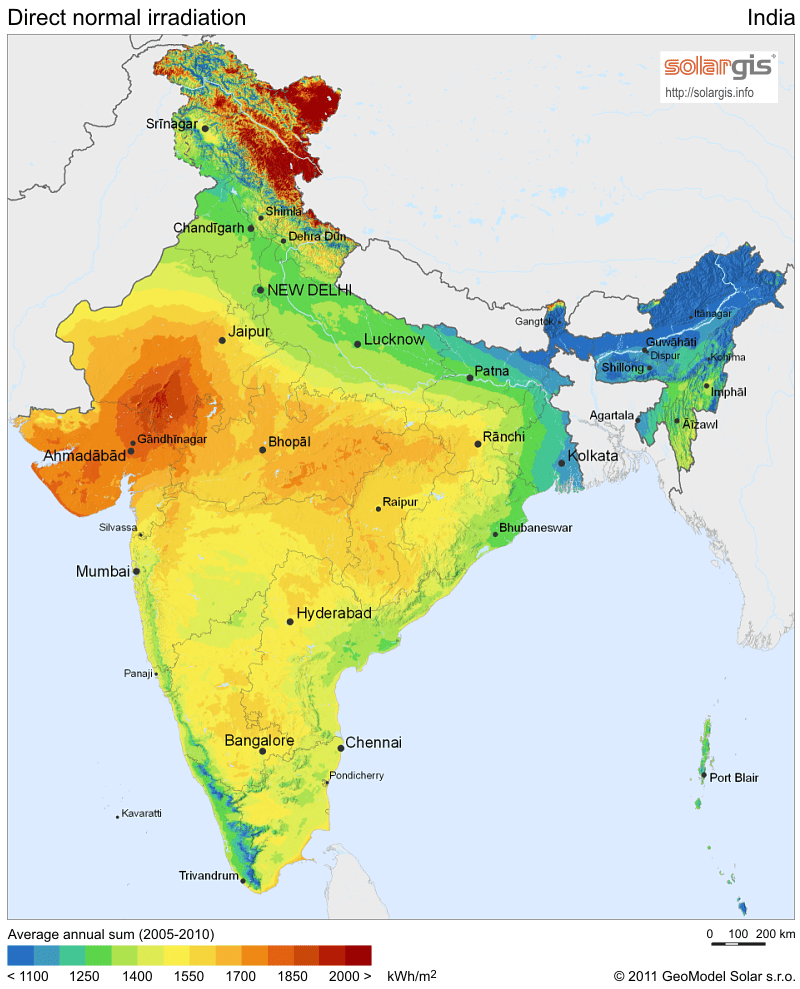

Of course, CSP to supply the EU would be sited in the sunny south with high DNI levels; in Spain, Portugal, Italy or Greece. Spain plans to auction for CSP this year. Lilliestam sees exporting power north from Italy as another promising option, because the power lines are already in place and capable of massive energy transfer both ways.

“Italy imports a lot of power today, all the way from France to middle and southern Italy. So if we were to add dispatchable capacity in particular in southern Italy, this would reduce the import need, thus “pushing” electricity northward and freeing up dispatchable hydropower from the Alps to balance growing wind and PV fleets in northern Europe. Solving problems in Italy may thus help solve balancing problems in other countries, too, by giving them better access to their own dispatchable resources,” he pointed out.

Greece would be even more interesting geopolitically, as it could be connected to different markets with fewer renewables in the new EU nations to its north; in Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia. And there it might really make a bigger difference: “because some Eastern European countries depend on Russian energy so much that they’re blocking the embargo plans – and finding ways to reduce that dependence may also reduce this political blockade” Lilliestam said.