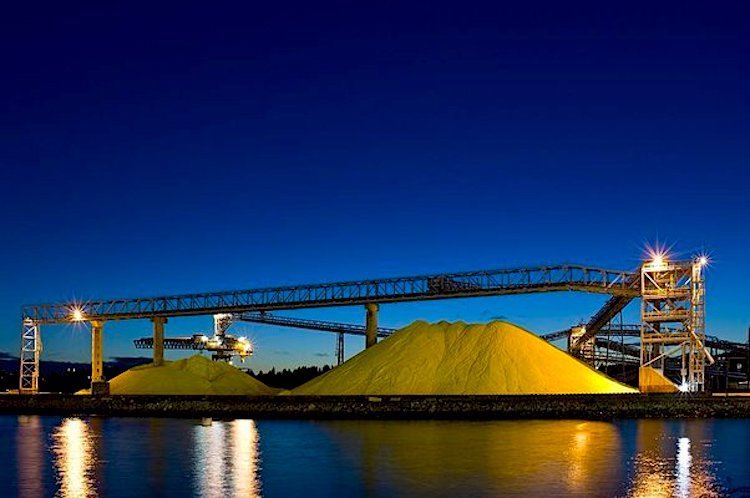

State Owned Enterprises can be very popular, especially when they yield an annual dividend to households as in New Zealand (Aotearoa is its indigenous Maori name). Here, Aucklanders protest a proposal to privatize them IMAGE @Cory Anderson

The USA seems like the most unlikely nation to nationalize a clean energy resource for the public good. So when one of the Democratic candidates announced a plan to do that, it was easy to dismiss the concept as pie in the sky. But in fact, a US government agency was once given a mission to do exactly that.

In the 1930s, WAPA – the Western Area Power Administration – was set up to market and deliver “clean, renewable, reliable, cost-based, federal” hydroelectric power – back at a time when hydropower was the only clean energy source.

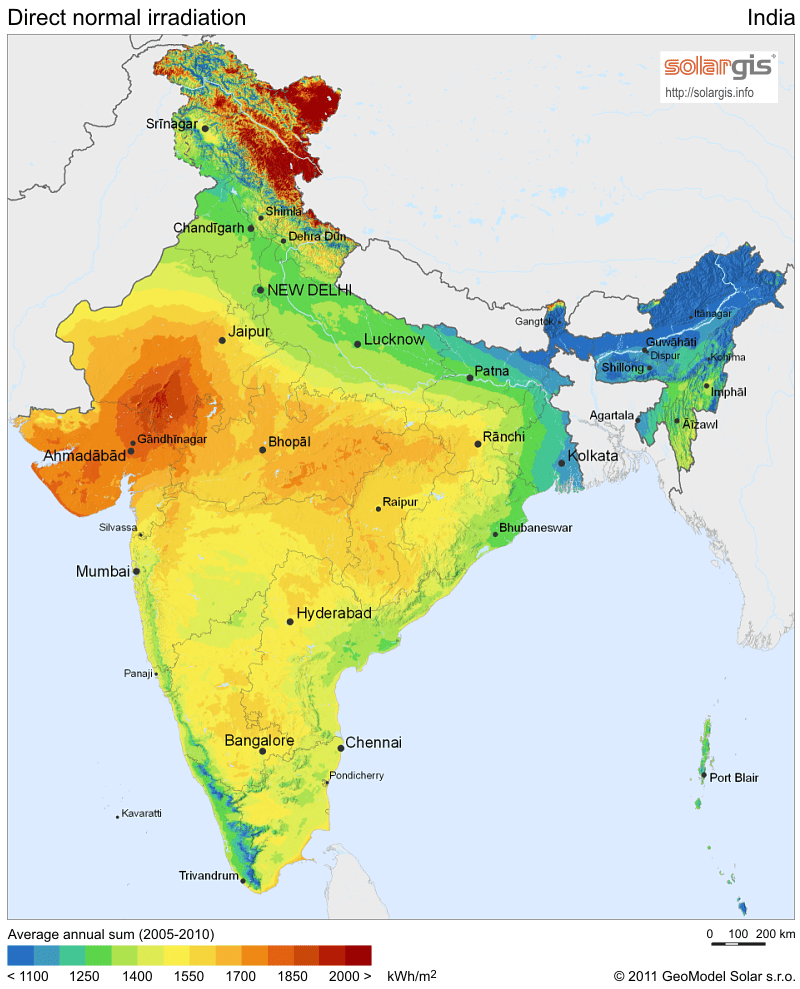

To this day WAPA remains commissioned specifically to supply hydropower. But with climate change, increasing drought will make hydropower a less abundant clean energy resource in the sunny southwestern portion of the nation that makes up WAPAs jurisdiction.

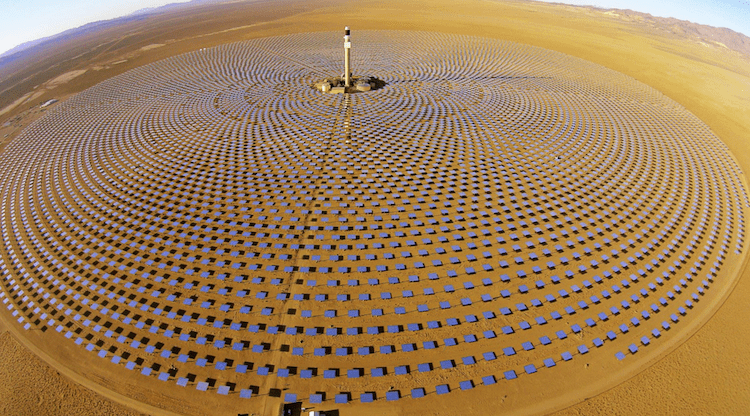

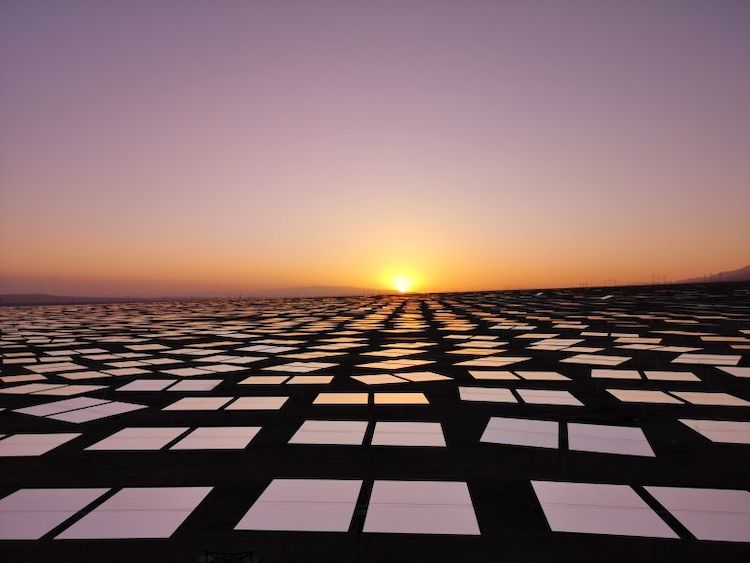

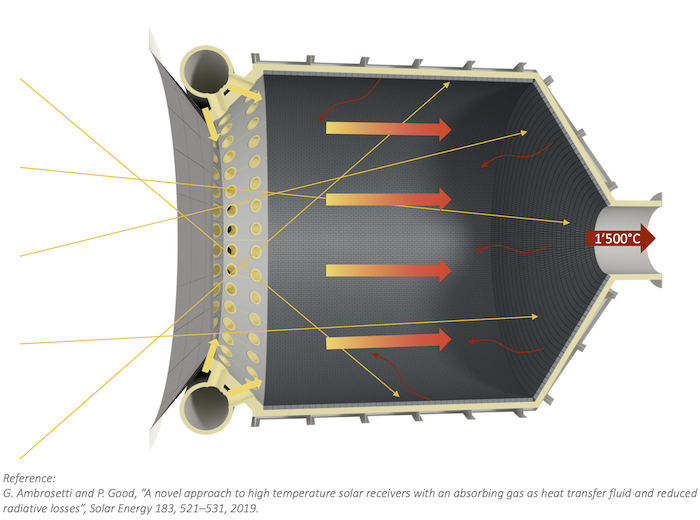

So what if WAPA were to be given an updated commission, to add a new clean energy source? Solar Dynamics CEO Hank Price, a veteran of the Concentrated Solar Power industry in the US, thinks CSP makes a good candidate. (How CSP works differently than the other solar; PV)

“We actually talked to WAPA about this and they said: “Well, we have a very specific mandate and we can’t go against that mandate,”” he commented. “But all it takes is legislation in congress to change that. So, congress could very easily have a mandate to build many gigawatts of CSP – and it doesn’t even have to be technology specific, but just opening up the opportunity for this would be great.”

WAPA’s mandate included electrification of the region. They built hydro dams as a joint purpose defined mandate and they serve a number of utilities, and co-ops and other groups with a least cost mandate.

Why use WAPA?

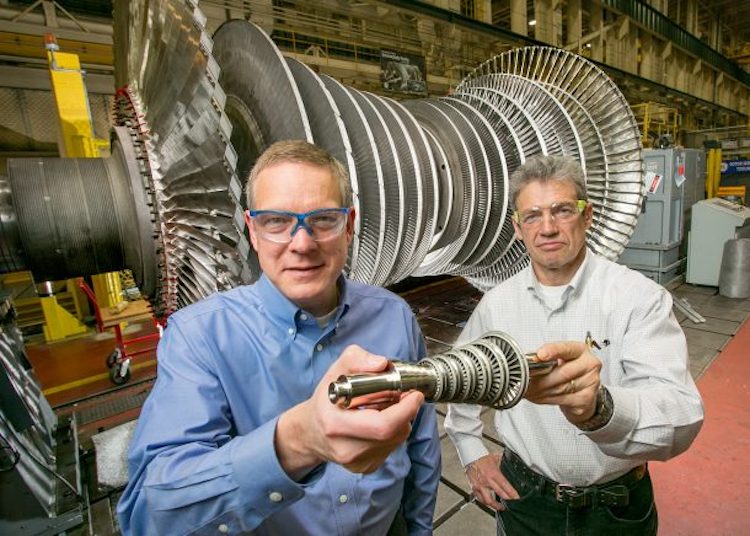

“WAPA is a real model because, like CSP, hydro was very expensive to site and build. So, they were able to cost it out to show that longterm it was cheap,” said Price who has co-authored a study of lessons learned from the first CSP plants. “And siting and building CSP plants is a little more challenging than PV or wind or fossil fuels, as you need experience on the power plant side and on the solar side and the interface between them.”

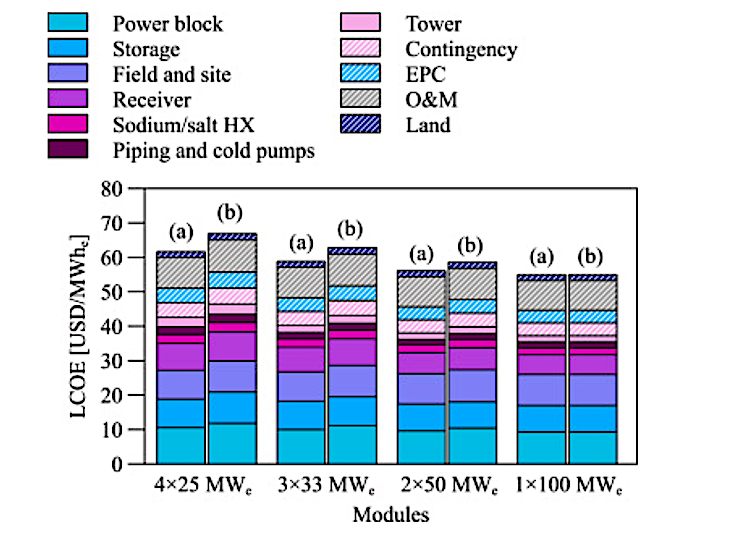

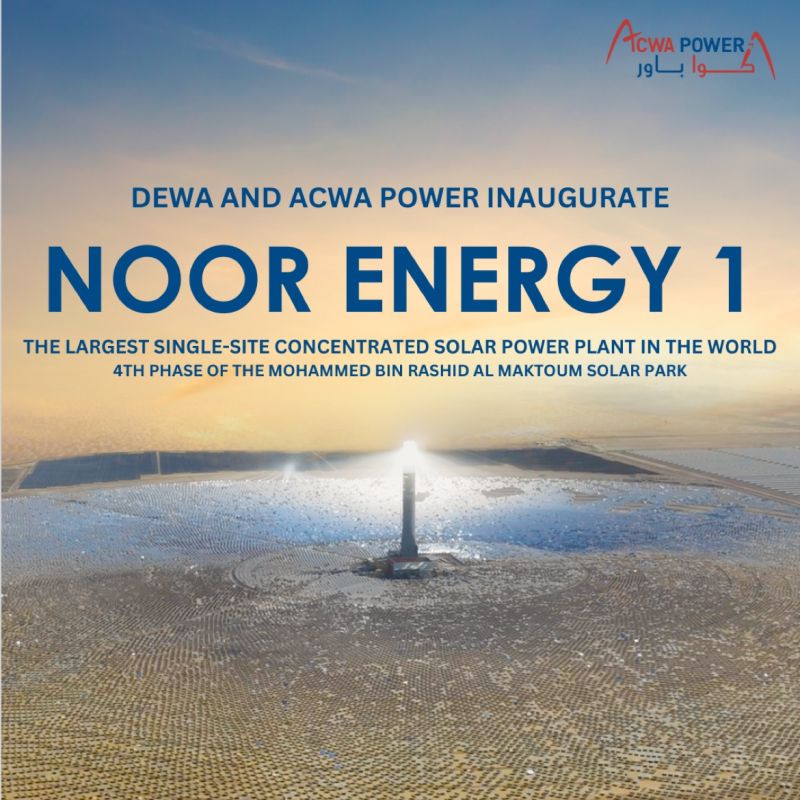

But the cost of siting, permitting and building CSP is upfront, and can be paid off in 20 years. WAPA is mandated to allow contract lengths of up to 40 years, which would benefit CSP, as shown by the longer contract ACWA Power signed in Dubai at 7 cents a kWh for firm solar day or night. When contracts are longer, prices can be lower because upfront costs can be amortized over a longer period.

“The plants in Dubai and Morocco are good examples of structures that drive down the cost, so I think more of that type of approach, where it is sort of a joint development between government and private industry is good. The Morocco model was very good,” Price explained.

Why not PV and wind?

The Sanders plan would have included PV and wind. However, these two clean energy sources are already well on their way to default energy supply as they are cheaper to build than thermal power like coal, nuclear and gas, and an entire supply chain ecosystem of manufacturers, developers, contractors and financiers has been developed. The private sector can already get these clean energy sources to market.

CSP on the other hand has many similarities to hydro in that both are more complex and expensive upfront but are able to operate reliably and cost effectively over the long term. Both are innately suited to supplying clean energy storage, hydropower by leveraging gravity and CSP through built in thermal energy storage.

Like hydropower, CSP generates clean energy from a power block. Both are a big undertaking, and these challenges have made it a bigger hurdle to develop CSP projects and drive costs down.

Could WAPA work as well as MASEN?

MASEN (Morocco Agency for Solar Energy) showed the world how to enable CSP projects to be built. It succeeded in building some of the largest CSP projects in the world, and achieving the 40% renewable target the Moroccan government set by 2020. The MASEN public entity model was a form of a public private partnership that determined what type of project was needed, identified the best sites, and tendered RFPs for competitively bid power purchase agreements. MASEN, which holds an equity share in the project as well as providing a portion of the project debt, acts as a middleman for the power, selling the power to the state-owned utility ONE. This allows Morocco to leverage private financing.

CSP projects are expensive to site and permit. Often CSP projects must be custom designed to meet the unique needs of the utility. This results in both a time and cost penalty for CSP projects and their developers. Each CSP developer wanting to bid on a power RFP must find and develop their own site prior to submitting a bid.

The MASEN approach takes the cost and risk of developing a project out of the equation. The government identifies and develops the site and prepares a detailed specification of requirements for a plant. Then CSP supply consortiums can competitively bid on a well-defined project.

WAPA’s mandate to get projects in the ground is very similar to MASEN’s. Both have been effective in getting projects built. Price however, proposes that instead of the government owning the CSP plants as is the case for many of WAPA’s hydroelectric projects, a public-private partnership should be used similar to the approach by MASEN.

The US government already has the Federal Loan Guarantee program that could be used to support financing projects. An example would be a model like that used for the DEWA project in Dubai where it’s a joint development, and by building several large CSP projects sequentially at the same site, costs were driven down a lot.

By simply adding wording to the legislation governing the energy source that WAPA can build, the US congress could expand the mandate beyond hydropower to encompass CSP – or other dispatchable renewable generation as well.

Another approach that could be considered is for WAPA to own the CSP plants outright. If built as public assets, dividends could be paid to ratepayers as New Zealand does from its state-owned energy or Alaska does from oil and gas. New Zealanders earn annual dividends of around $250 USD. Once there is that connection, state owned assets become very popular!

There are seasonal variations in CSP plant deliveries, and contracts in the US account for this. A developer will commit to generating a specified amount over the entire year, accounting for the fact that more is generated on average during summer than winter.

WAPA contracts also account for seasonal intermittency. Hydropower has seasonal fluctuations in how much water flows between stormy winters and dry summers. It has also set up contracts to supply non-firm energy, where the utility customer benefits from lower costs, but can be alerted to a shortage at short term notice.

Price brings his experience with the needs of the utility industry to this concept. Several years ago he designed and analyzed the economics of building a CSP plant as a solar peaker, after the concept was floated by the Arizona utility Arizona Public Service (APS), which since 2013 has experienced being able to control when the 280 MW Solana CSP plant runs off its stored thermal energy.

“Utilities were leery that peaker plants could be cheap, but APS has been interested in this idea. At the moment, there’s excess capacity but once you get rid of the fossil fuel plants, there will be a need for a large amount of new dispatchable capacity,” Price noted. In his study that he presented at the SolarPACES conference in Chile, he showed a way for solar peaker plants to be competitive with today’s gas ones.

Why public development would benefit CSP

The ability to create certainty is the argument behind commissioning a government entity like WAPA or MASEN to actually get projects in the ground. The many industries needed to create a CSP supply chain need to have faith in a future to develop new assembly lines to manufacture the new parts unique to CSP.

Researchers found that due to the uncertainty of the future of CSP in Chile; manufacturers among potential supply chain industries were reluctant to invest in new assembly lines, hampering even its current project, the 250 MW Cerro Dominador CSP plant. If there could be some certainty, then the supply chain would develop.

With its thermal power block, CSP plants have similarities to coal plants. These have been refurbished to run for 60 years or more, so their longevity is a benefit. And once sited, the solar resource is permanently assured at the site, with no fluctuating fuel costs, so longer contracts capture that benefit.

Price noted: “WAPA has a lot of power lines too, and many of them run to coal plants and so they are going to have power lines and no power once they start shutting down these coal plants. There is a lot of infrastructure that already exists and a lot of it is in good CSP regions; a fair amount is in New Mexico and Colorado and the Four Corners region in Arizona

As the US continues to shutter coal plants and as a destabilized climate depletes former hydropower resources, could a reimagined WAPA be given a new mission, a century after its 1930s beginnings in The New Deal?