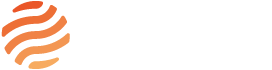

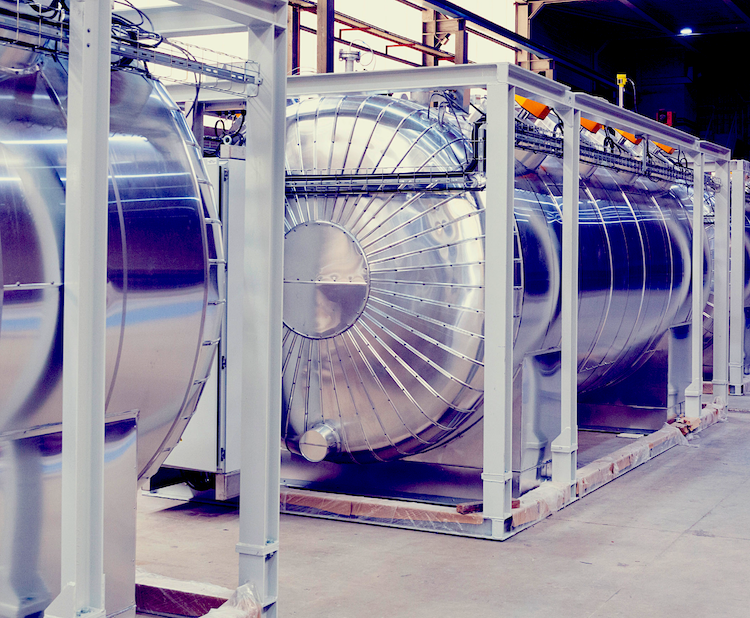

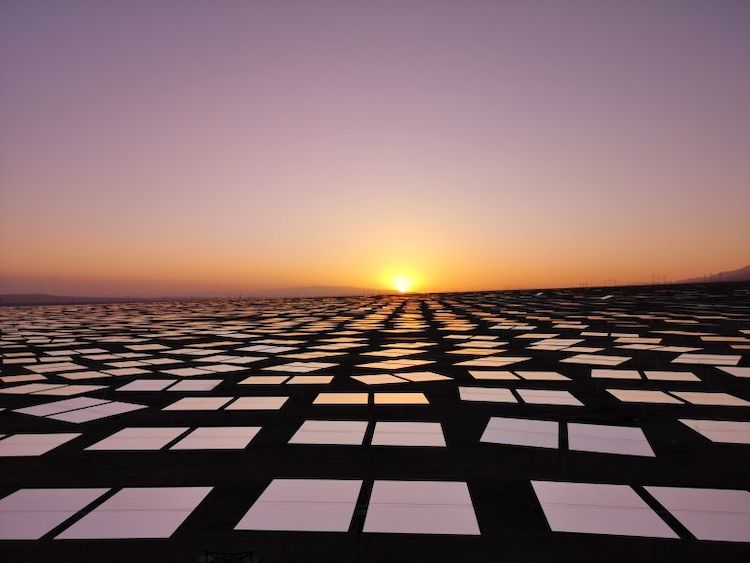

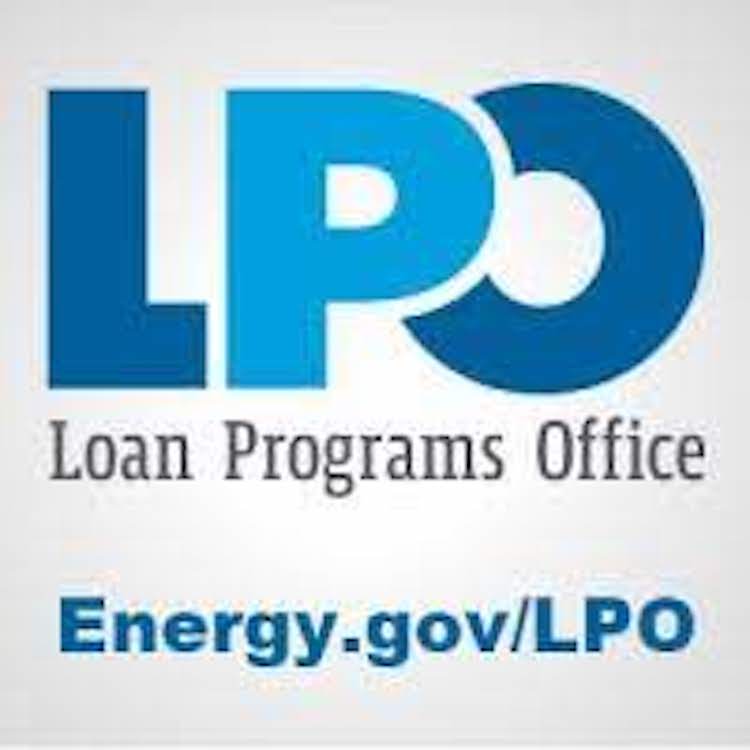

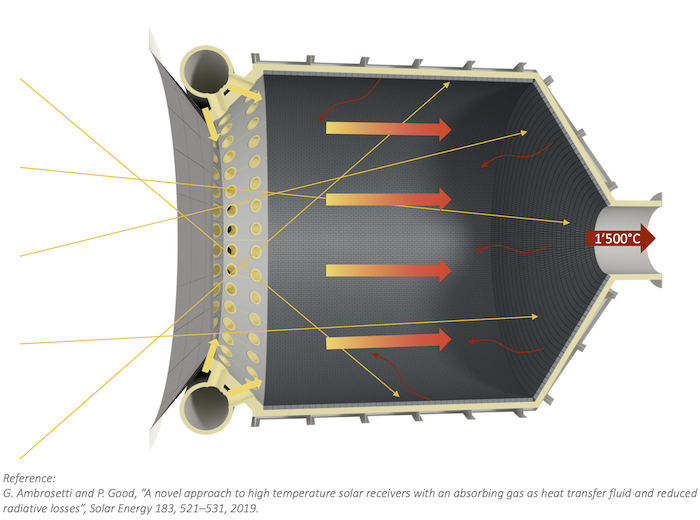

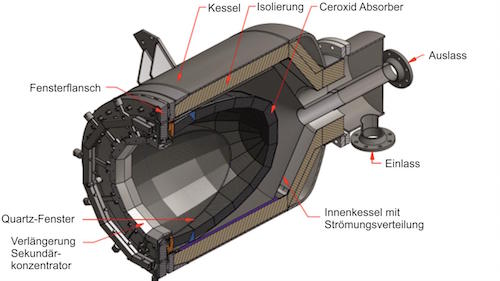

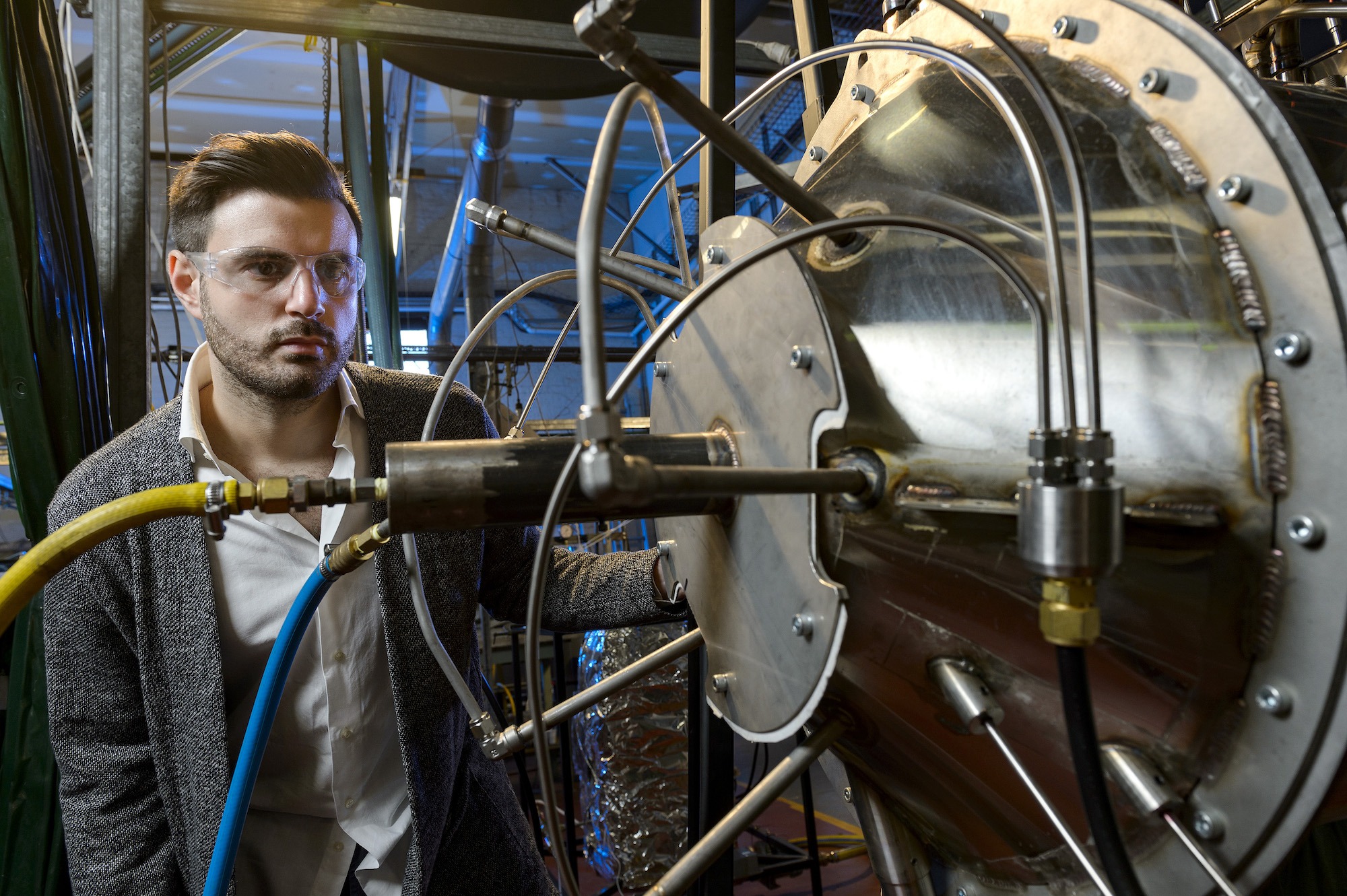

The Hybrid Solar Receiver Hydrogen Combustor for mining processes at 800°C Working closely with companies such as Alcoa, BHP, GFG and OZ Minerals, the CET team has demonstrated at lab scale that their combination fuel combustor/solar reactor is fuel-agnostic: it can operate 100% on solar radiation or 100% by fuel combustion, or on any combination of the two heat sources, as a direct hybrid. IMAGE@ A. Chinnici University of Adelaide Centre for Energy Technology

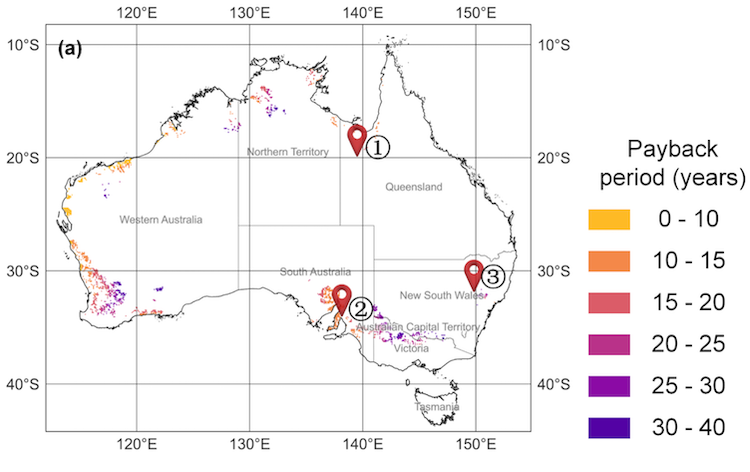

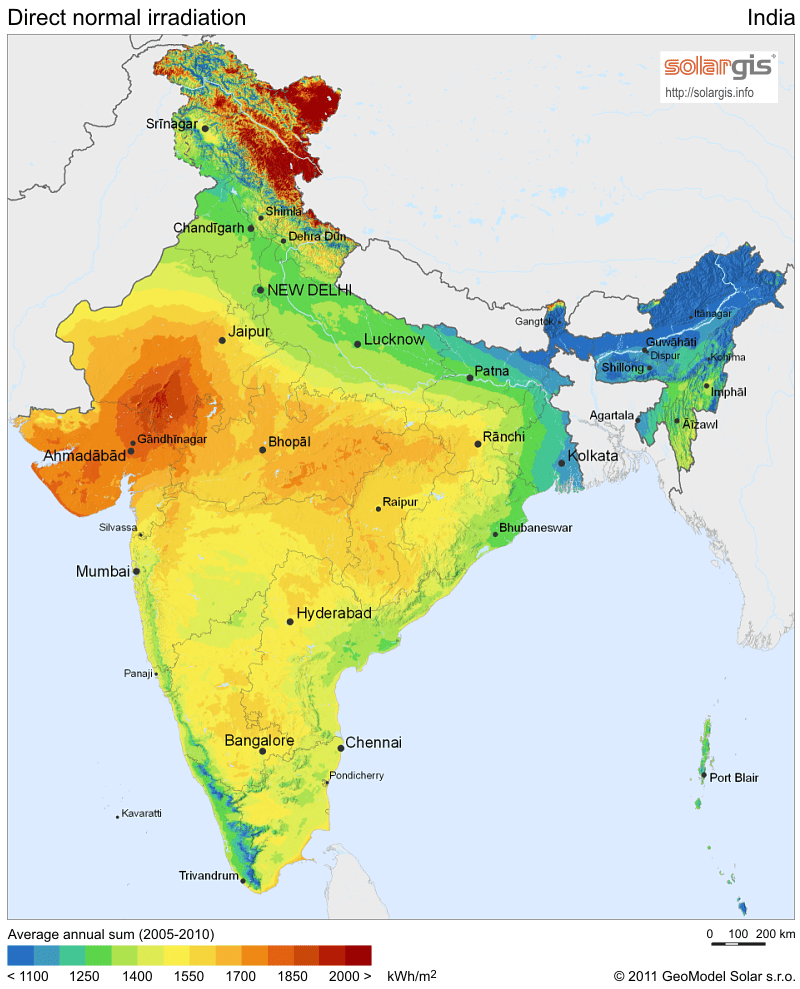

Direct solar heat – Concentrated Solar Thermal (CST) – is a potential renewable resource for replacing heat from burning fossil fuels for industries like mining, as its technologies generate heat directly from sunlight at anywhere from 150°C to 1500°C. But lack of information on both sides stands in the way of CST being used for mining processes, according to the authors of a paper just published at Applied Energy.

“In our conversations with the mining industry and others, the challenge that they’re having is they don’t know how renewables could be specifically applied in their operations,” said Jill Engel-Cox, who directs NREL’s Joint Institute for Strategic Energy Analysis and is an author of the report Integrating renewable energy into mining operations: Opportunities, challenges, and enabling approaches

“So there’re a lot of questions on the industry side of how they would work, the financing, the versatility, and then the reliability and resilience of the technology itself. The industry is pretty conservative about how they use and generate power,” she observed.

CST firms for their part have yet to tap the potentially massive opportunities for renewable heat for the mining industry, especially downstream from extraction, according to solar finance expert Travis Lowder, a Project Manager with NREL’s Integrated Applications Center, who commented that the industry remains focused on power.

“In the conversations we’ve been having with them and the solar industry itself, there seems to be a lack of a business model; it is not there yet,” he said. “Serving industrial customers is still something that’s considered rather new and right now we find that there’s just not a great understanding about how solar thermal energy can serve the mining industry. So there needs to be business model development about how you address the needs of industrial processes.”

Variety of CST technologies needed for different processes

Lowder noted that no one technology is going to win the day, there’re going to have to be a lot of configurations and applications to meeting the diverse needs of an industry like mining and metals processing.

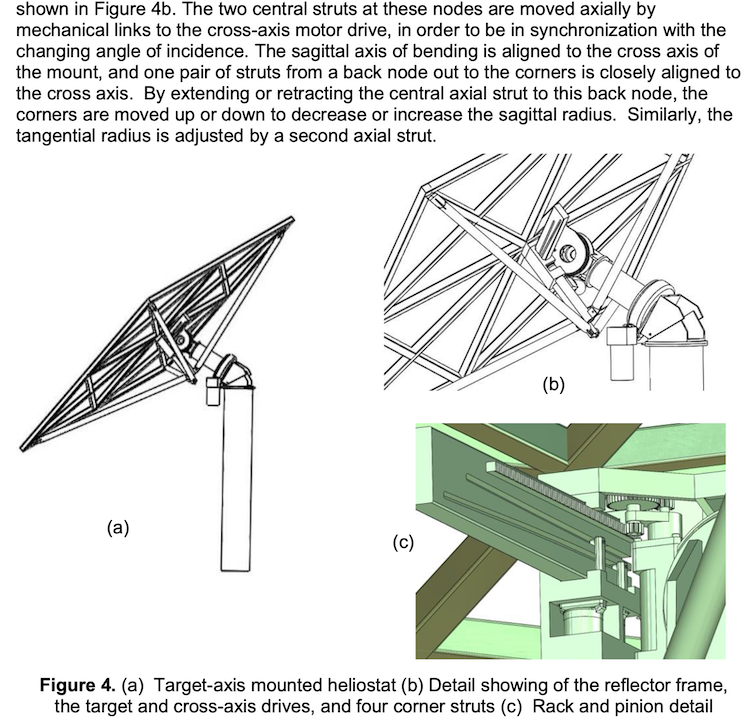

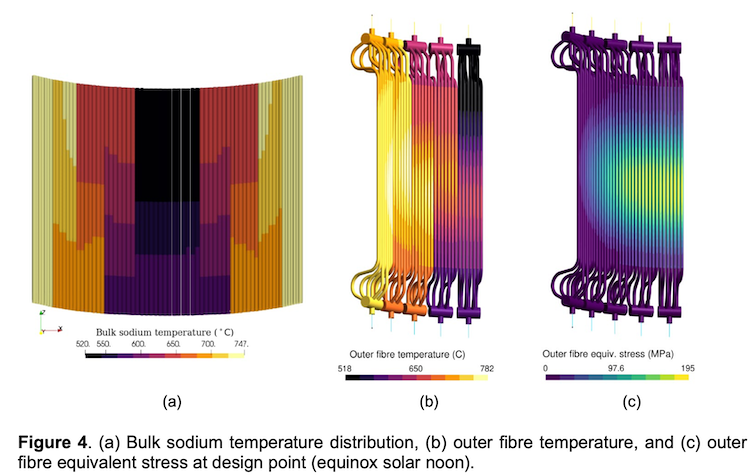

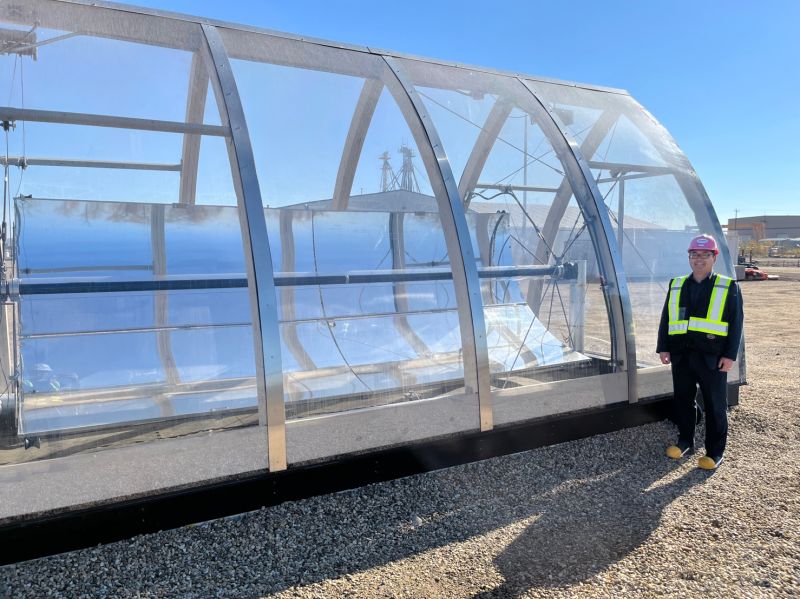

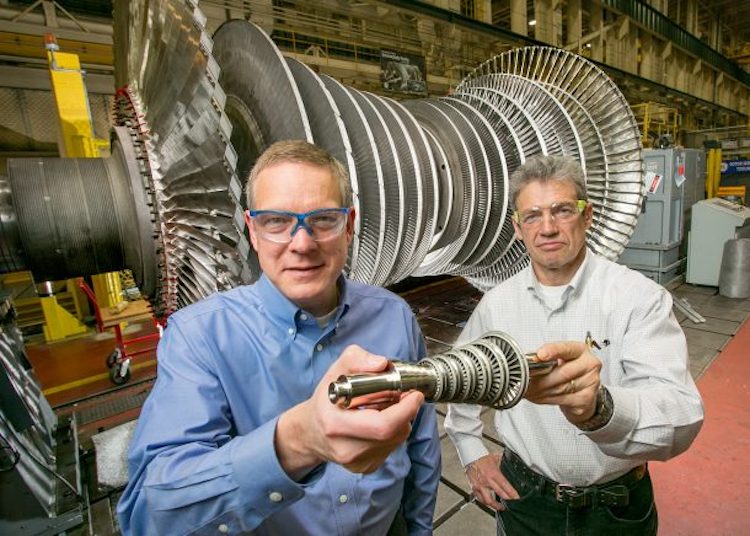

Some examples of the variety of solar thermal configurations that could be applicable for supplying heat for mining processes include Fresnel modules coupled to a turbocharger to provide high temperature air for drying processes at 400°C, or a solar reactor hybridized with a hydrogen flame at 800°C in Australia for mining processes or high temperature thermochemistry in solar reactors at 1500°C for supplying solar heat directly for cement manufacturing while capturing the carbon naturally emitted during limestone calcination.

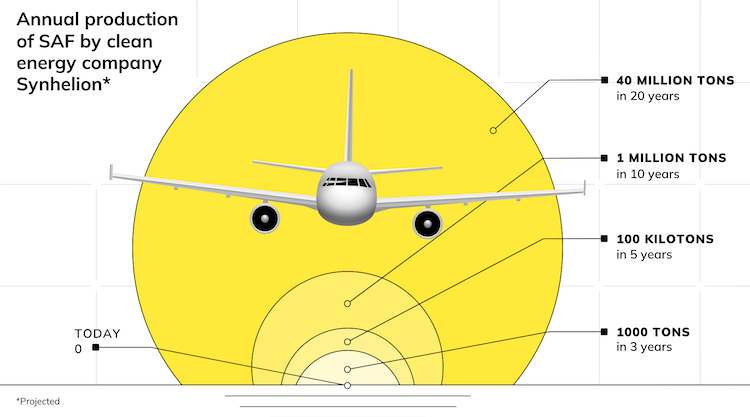

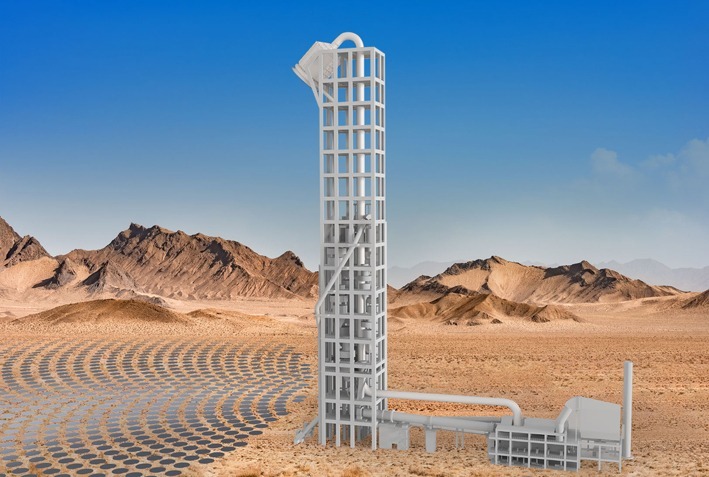

Synhelion to supply solar heat to CEMEX for cement production while capturing CO2 “As our own process for making solar fuels is designed to feed in CO2, it is easy for us to extract the CO2 emissions from the calcination reaction in practically pure form.” IMAGE@Synhelion

“We wouldn’t just be looking at the initial ore melting phase or the Bauxite reduction phase. It could be that CST and other renewable technologies are suited for specific parts along that process,” explained NREL Cost and Systems Analyst Parthiv Kurup.

“With DLR and NREL, we’re discussing some potential work, on the use of CSP for processes, such as manganese sintering, and ore sintering which don’t necessarily require as high temperatures. There are intermediate steps and processes which would be very suitable for CST to provide the renewable heat.”

Need for a different business model

Lowder’s background was with the PV industry, which was able to leverage power purchase contracts to meet renewable mandates to rapidly grow deployment. Once built, solar and wind farms remain in place generating for the full term of a 20-year contract, and likely beyond.

“So I and others in this space have been looking at how the business model of heat would need to change for selling it as an industrial product effectively,” said Kurup, a co-author on the NREL publication Opportunities for Solar Industrial Process Heat in the United States.

“A heat purchase agreement we’re sort of naming it. Heat as a service perspective helps to decouple the capital expenditure outlay of the CST plant. We’re seeing that in Europe. There are companies now out that are using ESCO models for heat to be able to provide heat directly as a contract, similar to a power purchase agreement.”

However, according to Engel-Cox, signing purchase contracts with a mine, as opposed to with an industrial site brings another key challenge.

”How long is the mine going to operate? That is the other piece that we heard about; there is a variability of demand,” she pointed out. “A mine will frequently last for decades, but it may run for five years at full scale then it might shut down half way for a few years, then it might be shut down completely, and then it might open up. When you have a fossil fuel source; you can have it on when you need it and you can turn it off when you don’t. But with renewables if there’s a contract you have to accept purchasing the energy over a 20-year lifetime.”

So her team found mining companies had a lot of hesitation in agreeing to large heat or power contracts when they couldn’t necessarily predict their energy needs over a long time period. “If the price of their mined product has dropped precipitously and the mines can no longer operate profitably, they’ll scale back, so they don’t always necessarily operate at full scale all the time” she said.

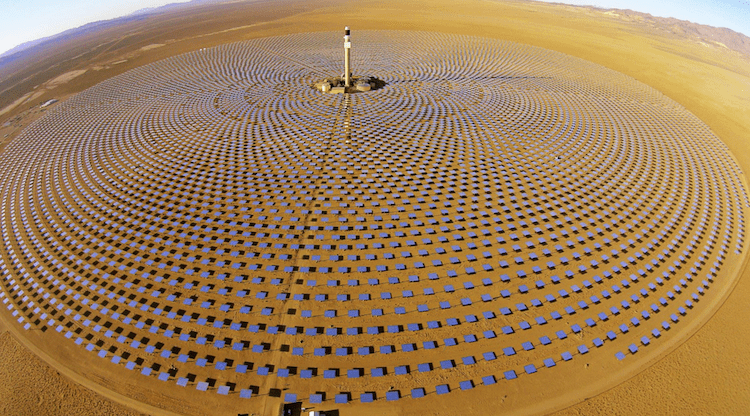

IMAGE@SolarReserve Proposed 450 MW Likana CSP project to supply Chilean mining industry (recently sold to EIG Partners which bid Likana at under 4 cents/kWh for day/night solar in Chilean auctions in 2021)

The other problem is that since mines tend to operate in remote areas, and often form the major demand in that area (at least at that scale) a CST firm, even with a relatively mobile, modular system, wouldn’t be able to adapt to down times by moving its solar equipment to another industry or community nearby. If heat could be provided to an industrial cluster, then potentially a drop in thermal demand could be offset by routing to other industrial sites.

A side business supplying solar hydrogen?

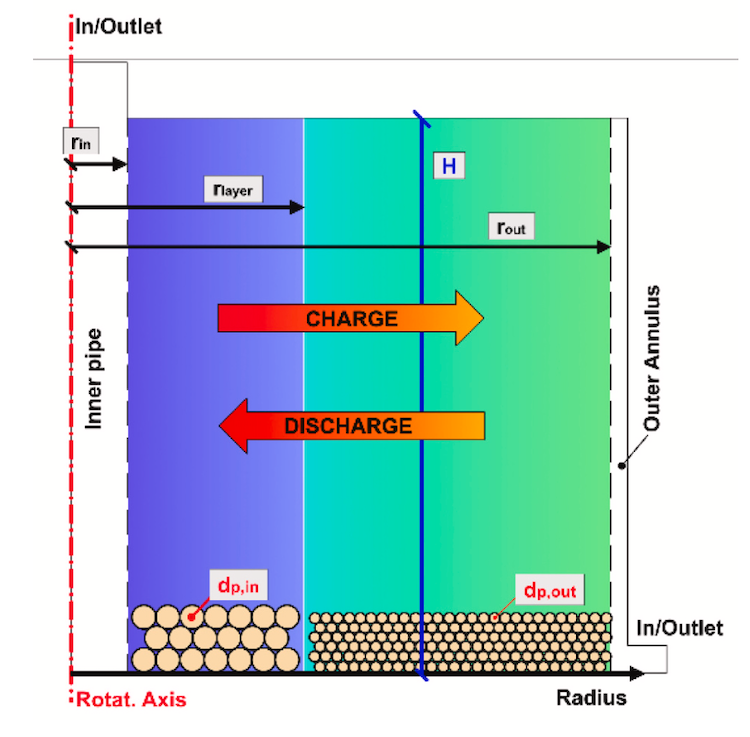

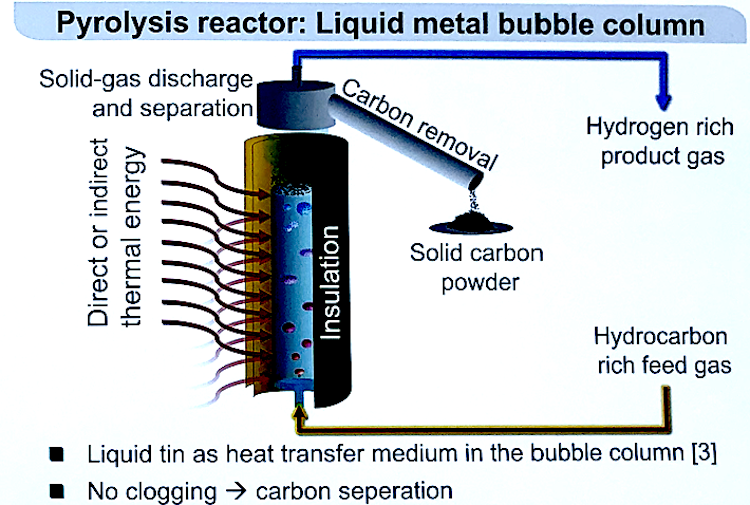

However, based on the portability of hydrogen, a solar hydrogen pilot from DLR might offer one solution for one kind of mine – copper. DLR’s Hybrid-Sulfur (HyS) project innovated a solar thermochemistry technology that produces 100% solar hydrogen by decomposing it out of sulfuric acid (H2SO4) in a 2-step circular process, with a solar reactor heated by a solar field of concentrating mirrors.

During copper ore processing, sulfuric acid is also generated indirectly and copper mines purchase hydrogen to use during the desulfurization process. The HyS technology would make solar hydrogen onsite instead from the H2SO4, using its solar field and solar reactor. So if the copper mine is not operating, it could continue producing this solar hydrogen, but deliver it to others, because hydrogen can be shipped on trucks or pipelines (and Caterpillar will offer generators that run on hydrogen this year).

“You’re going to want to get a return on your investments by running that thing as often as you can producing as much material as possible because of the capital intensity of that asset,” Lowder noted.

Whatever the solution, the bottom line is a need for market research to find out what would work for all parties involved, Engel-Cox concluded.

“I think if CSP wants to reach the industrial sector, and I think it has promise there, because of the ability to provide heat that PV does not – or there has to be some sort of an intermediary – I think the industry needs to be talking to the industries that have these demands and be able to adapt their technology and their business models to meet those industrial requirements. That just takes a lot of conversations and potentially some pilot projects to make it work.”